Roomba’s bankruptcy proves what robotics pioneer Rodney Brooks predicted: billions in humanoid robot funding face the same fate as his failed company

The Brief

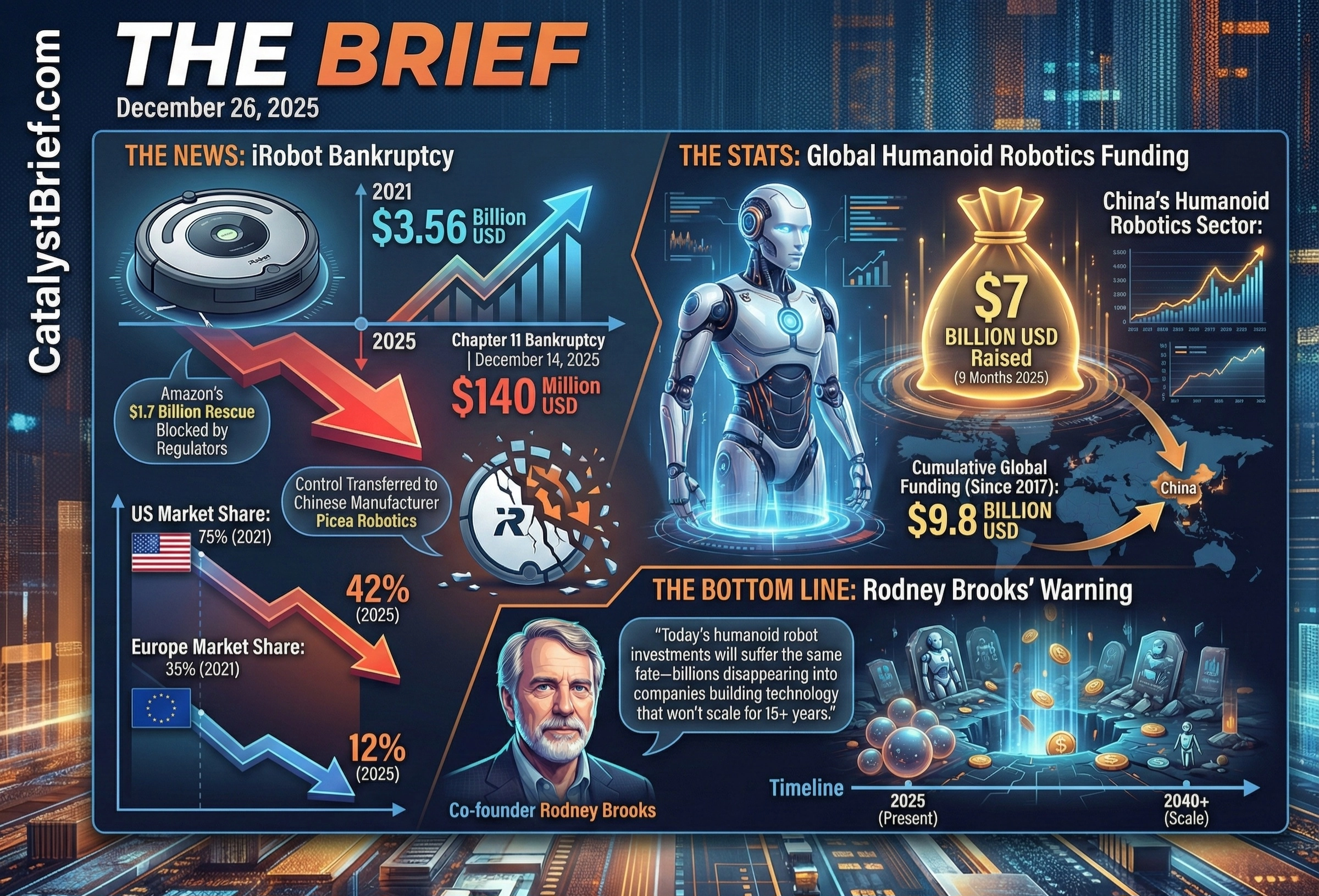

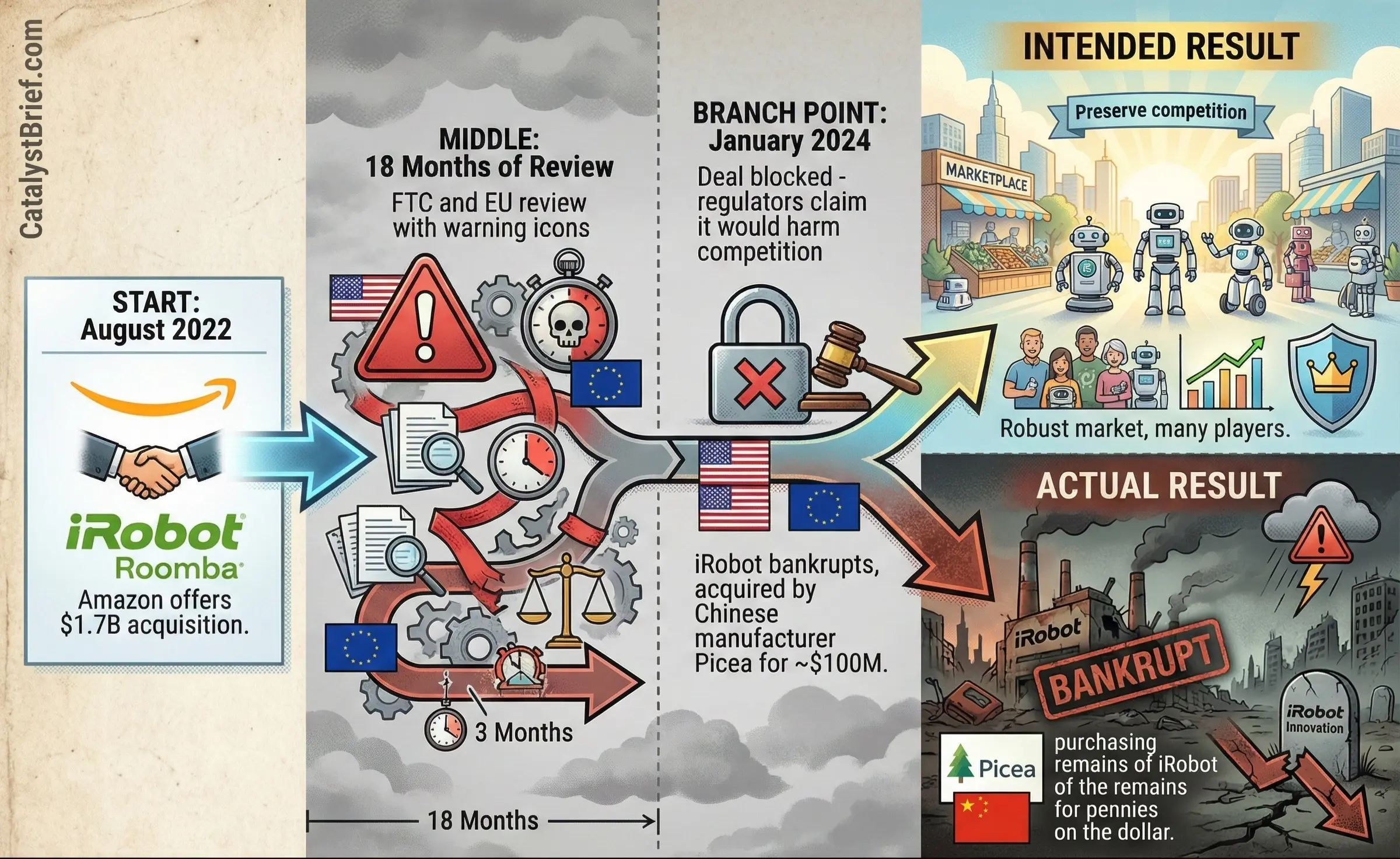

The News: iRobot filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy on December 14, 2025, transferring control to Chinese manufacturer Picea Robotics after regulators blocked Amazon’s $1.7 billion USD rescue acquisition.

The Stats: The company’s value collapsed from $3.56 billion USD in 2021 to $140 million USD. Market share plunged from 75% to 42% in the US and 35% to 12% in Europe. China’s humanoid robotics sector raised $7 billion USD in nine months of 2025, while cumulative global funding since 2017 hit $9.8 billion USD.

The Bottom Line: The bankruptcy of Roomba’s creator validates warnings from co-founder Rodney Brooks that today’s humanoid robot investments will suffer the same fate—billions disappearing into companies building technology that won’t scale for 15+ years.

The Catalyst

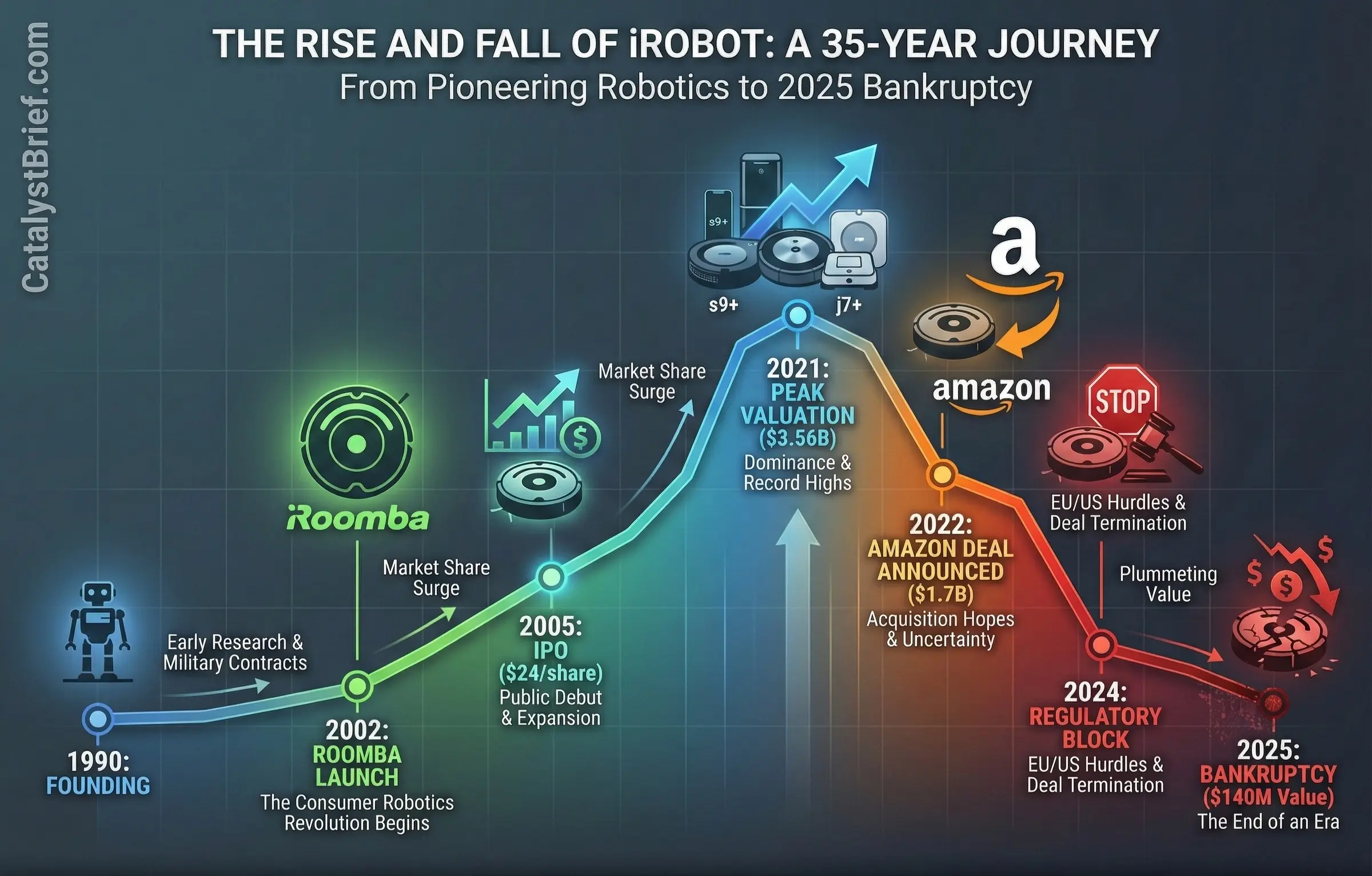

On December 15, 2025, Colin Angle stood in front of cameras and called his company’s bankruptcy “nothing short of a tragedy for consumers.” The former CEO wasn’t exaggerating. iRobot, the company that popularized consumer robotics and sold over 50 million Roombas, had just filed Chapter 11—transferring control to its Chinese contract manufacturer for roughly $100 million USD after regulators killed Amazon’s $1.7 billion USD acquisition offer.

But here’s the detail that should terrify anyone betting on humanoid robots: one of iRobot’s three co-founders spent September warning that billions in humanoid investment would vanish the exact same way.

Rodney Brooks—MIT roboticist, founding director of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, and the mind behind iRobot’s behavior-based approach—published his assessment three months before his own company collapsed. The timing creates an uncomfortable question for the 150+ companies chasing humanoid deployment: if Brooks couldn’t save the robotics company he built, why would his warnings about humanoid economics be wrong?

The Prediction That Just Got Validated

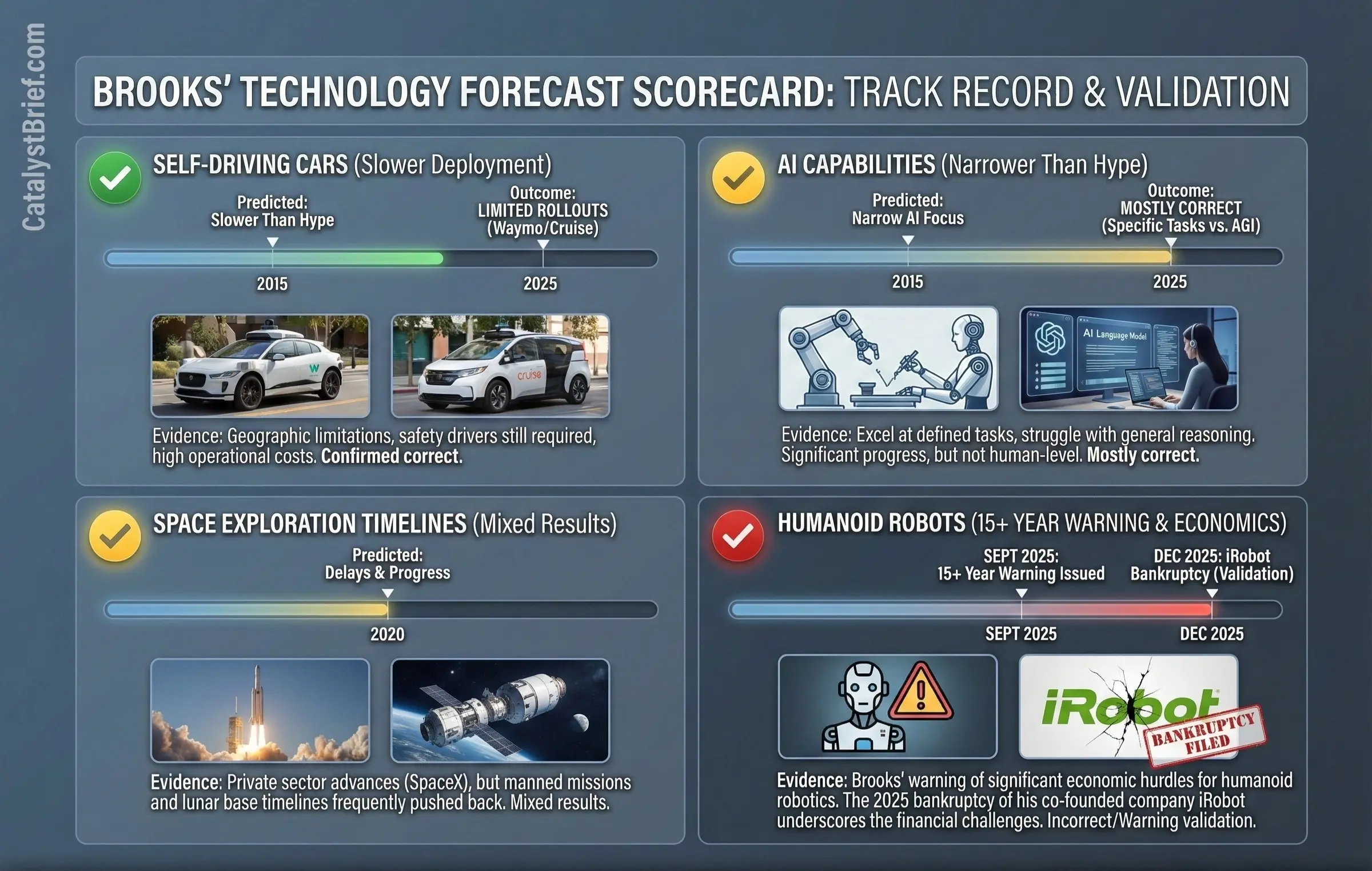

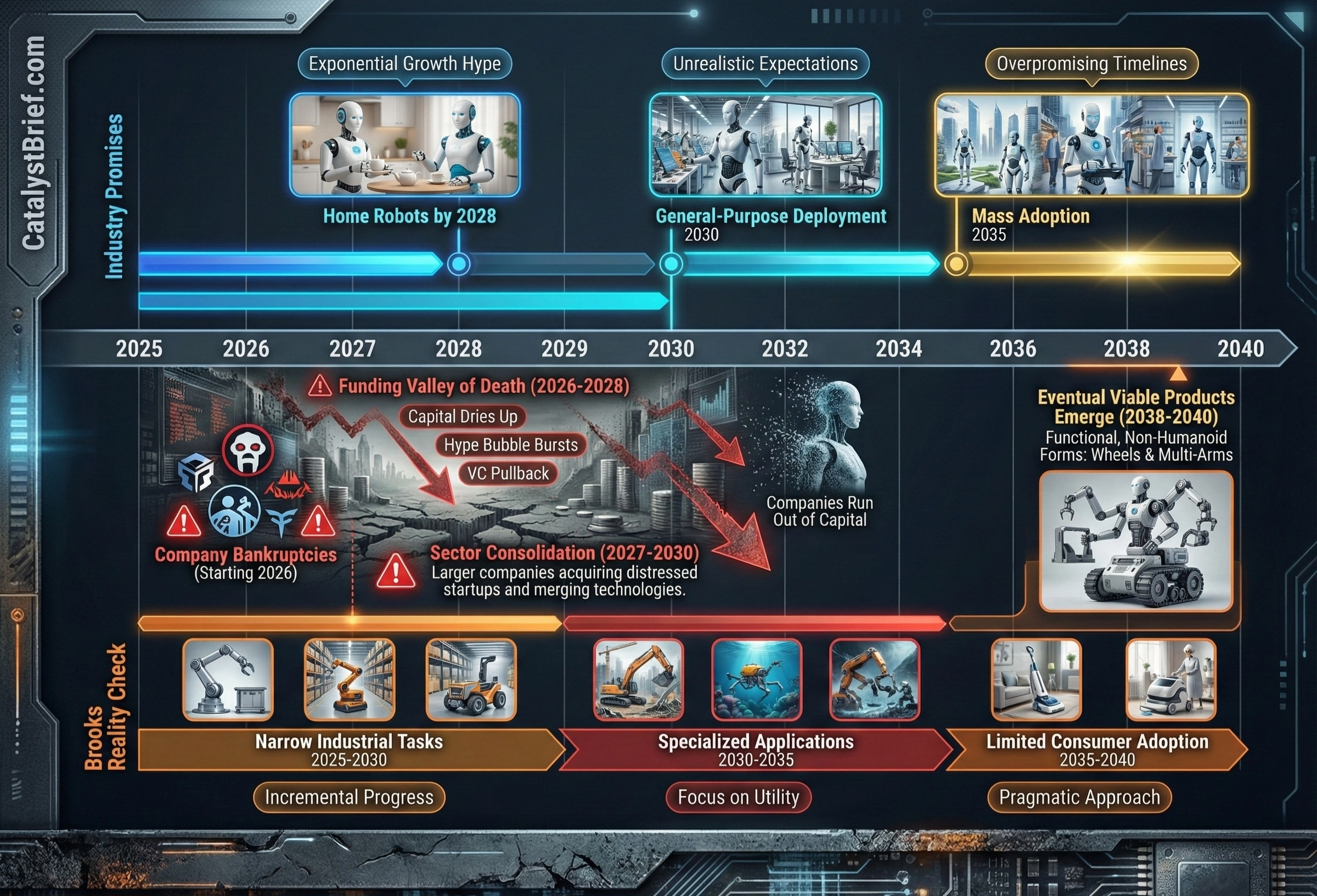

Brooks’ September blog post wasn’t gentle. He declared that training humanoids through video demonstrations was “pure fantasy thinking,” that current platforms would be “long gone and mostly conveniently forgotten,” and that deploying dexterous humanoids at scale remained 15+ years away.

Three months later, his own company proved the point. iRobot’s bankruptcy filing revealed $100 million USD owed to Picea Robotics, $3.4 million USD in unpaid tariffs, and between $100 million to $500 million USD in total liabilities. Revenue had crashed 33% year-over-year in the latest quarter. The company that once commanded 75% of the US robot vacuum market now held just 42%—overtaken by Chinese competitors like Roborock, Ecovacs, and Dreame.

The parallel to today’s humanoid boom is precise. Chinese manufacturers entered with lower costs, faster iteration cycles, and protected home markets. By the time iRobot responded, the cost gap had become insurmountable. Roomba vacuums, manufactured in Vietnam, faced new US import tariffs that added millions in costs. Chinese competitors manufacturing domestically or through different supply chains undercut on price while matching or exceeding features.

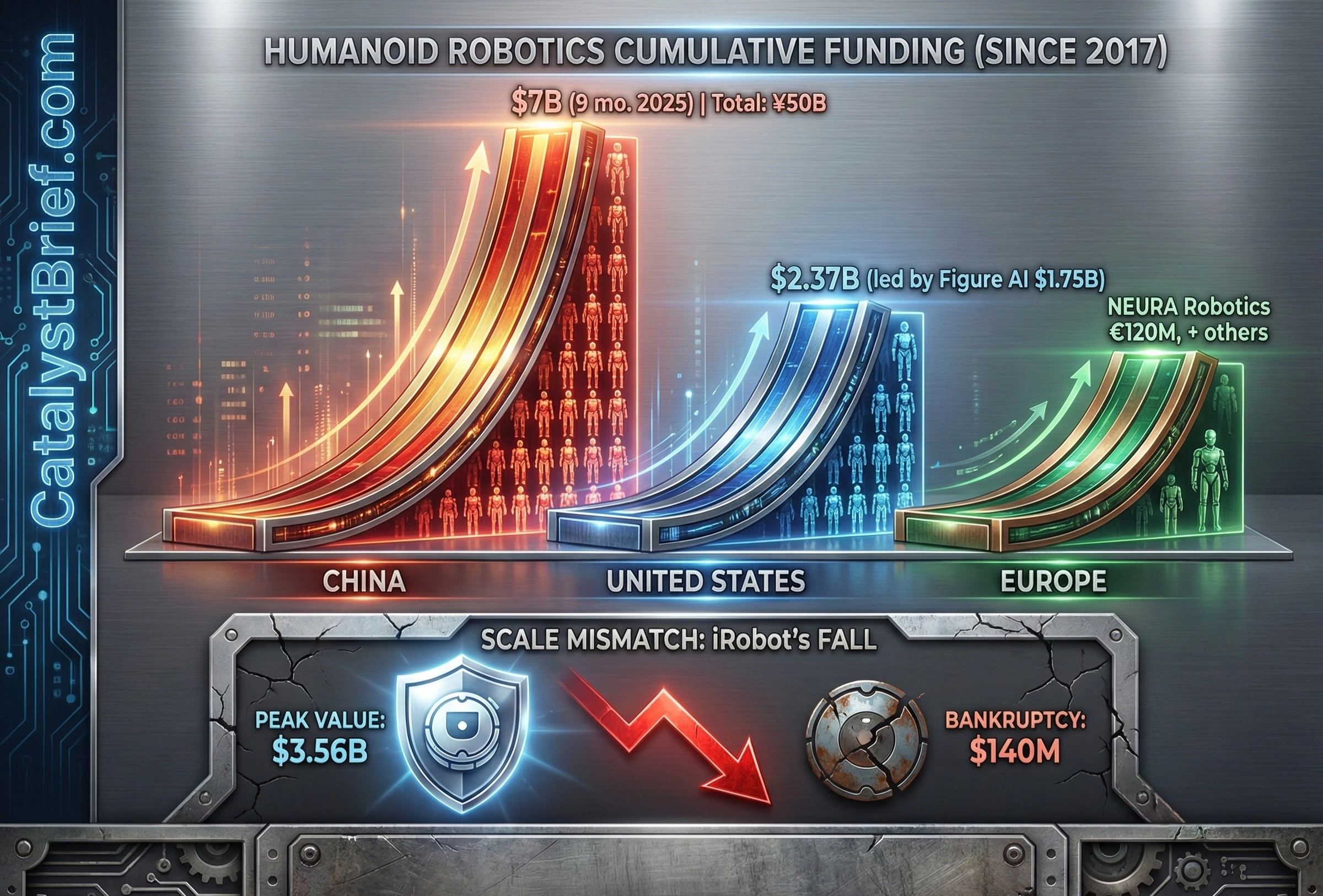

Now apply that pattern to humanoids. Figure AI raised over $1 billion USD in September 2025 at a $39 billion USD valuation. Tesla targets 100,000 Optimus units by 2026. Apptronik secured $403 million USD. Total sector funding hit $6 billion USD through mid-2025, with projections reaching $9.8 billion USD cumulatively since 2017.

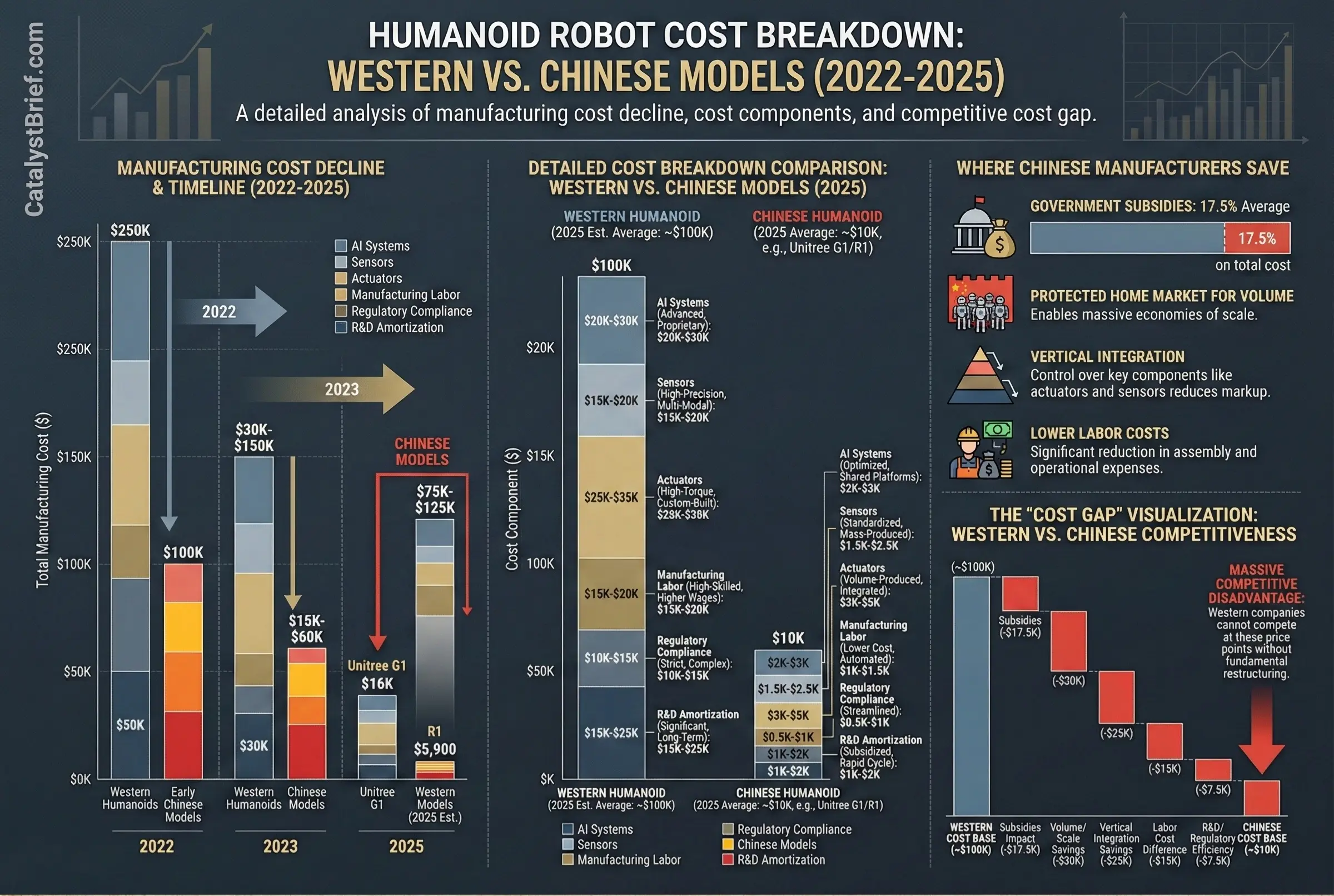

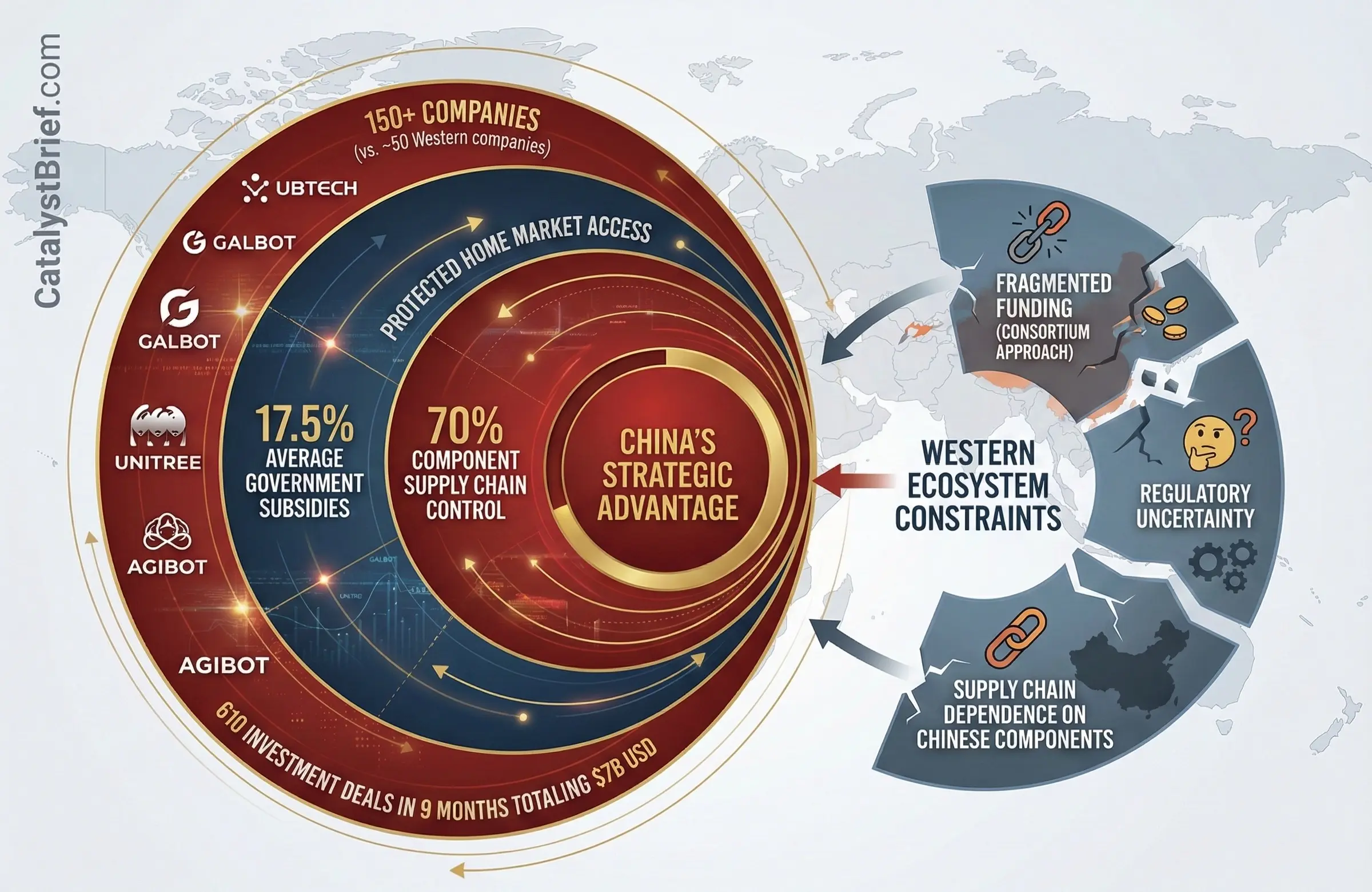

Meanwhile, China executed 610 robotics investment deals totaling 50 billion yuan ($7 billion USD) in just the first nine months of 2025—a 250% year-over-year increase. Chinese manufacturer Unitree shocked Western competitors by launching its G1 humanoid at $16,000 USD, then the R1 model at just $5,900 USD in July 2025—price points Western analysts said were impossible for years.

The math problem is identical to what killed iRobot: Western companies burning capital to perfect expensive technology while Chinese competitors iterate faster at lower costs with government backing and protected markets to validate products.

The Technical Reality Check

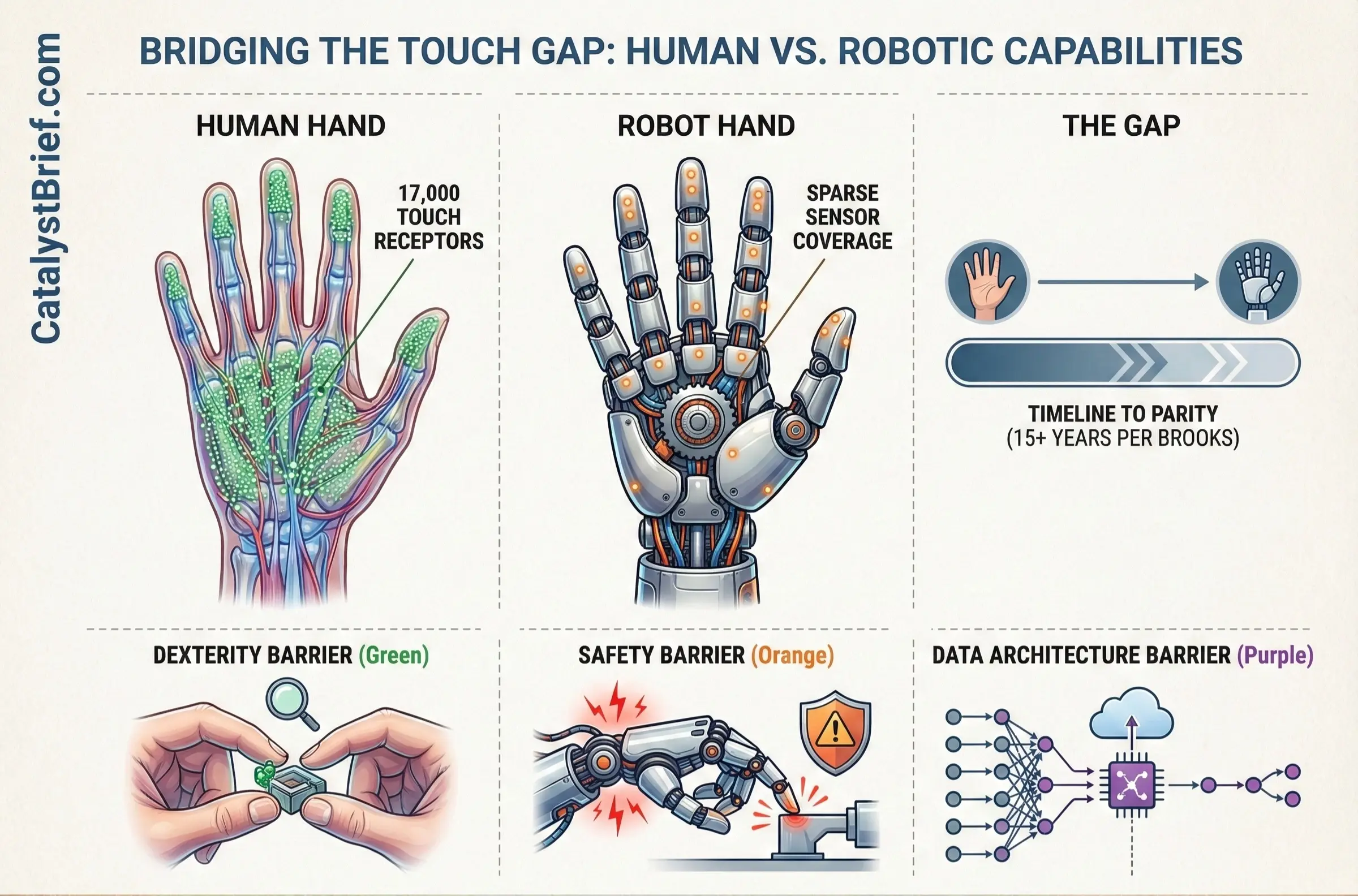

Brooks identifies three fundamental barriers that make humanoid timeline projections unrealistic. Each deserves scrutiny because they explain why iRobot-style collapses might be inevitable.

Dexterity Gap: Human hands contain approximately 17,000 specialized touch receptors. Current robot hands don’t approach this sensitivity. Brooks argues that showing robots videos of humans performing tasks—the core strategy at Tesla and Figure—fundamentally misunderstands the problem. Vision AI succeeded because decades of camera technology and image data already existed. “We don’t have such a tradition for touch data,” Brooks wrote.

The December Humanoids Summit in Mountain View, California, validated this concern. Skild AI co-founder Abhinav Gupta noted that “no one shows you climbing stairs when it comes to these humanoids.” When actual robots arrived at the conference, handlers controlled them and herded them into elevators to avoid stair challenges. The gap between promotional videos and operational reality remains vast.

Safety Crisis: Full-sized bipedal robots pump massive energy into maintaining balance. When they fall—and they still fall frequently—they’re dangerous. Brooks warns to “stay at least 3 meters away from walking robots.” Physics compounds this problem: a robot twice the size of current models packs eight times the harmful kinetic energy.

Industrial robots have decades of safety protocols precisely because they’re dangerous. Humanoids introduce novel risks: they navigate dynamic environments, work near untrained people, and require constant power for stability. The regulatory frameworks don’t exist yet. Insurance models haven’t been priced. Liability structures remain undefined.

Wrong Data Architecture: AI breakthroughs in speech and vision leveraged existing data collection infrastructure built over decades. Touch sensing for manipulation has no equivalent. Creating that infrastructure—sensors, data formats, training pipelines, validation methods—represents a multi-decade research program, not a capital deployment problem.

This explains why China’s TARS Robotics made headlines with a December 22 demonstration of a humanoid performing hand embroidery. The achievement is real—threading needles and stitching logos requires sub-millimeter precision with soft, flexible materials. But TARS founded in February 2025, demonstrates how rapidly Chinese companies can move from concept to working prototypes, while Western companies burn capital on longer development timelines.

The Economic Reality Emerging

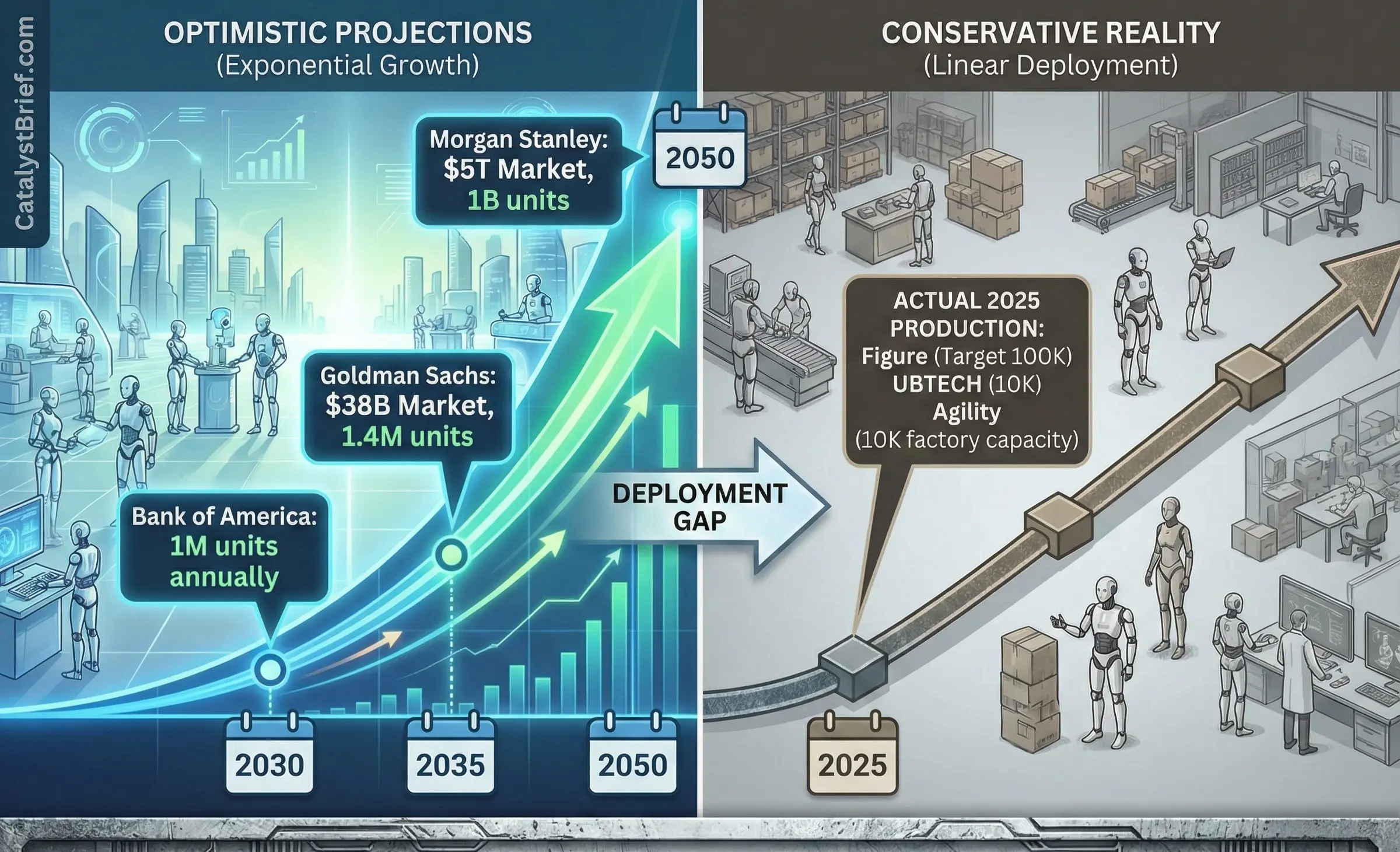

Market projections create momentum, but Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley forecasts reveal the timeline disconnect. Goldman projects $38 billion USD by 2035 and 1.4 million unit shipments. Morgan Stanley forecasts $5 trillion USD by 2050 with 1 billion units deployed.

These are 10 to 25-year horizons. Companies raising at multi-billion valuations today need revenue trajectories that justify those valuations within typical venture timeframes—7 to 10 years. The math doesn’t work unless humanoid deployment accelerates far beyond current technical capabilities.

Consider the production reality: Tesla targets 5,000 Optimus units in 2025, scaling to 100,000 in 2026. BYD aims for 1,500 humanoids in 2025, ramping to 20,000 by 2026. Shanghai-based Agibot targets 5,000 units in 2025. Even if all these companies hit their targets—an optimistic assumption—total 2026 production barely exceeds 100,000 units globally.

At $25,000 USD average selling price (Goldman’s 2035 projection), that’s $2.5 billion USD in revenue across the entire sector. Divided among dozens of competitors, with manufacturing costs still high and limited deployment scope, the path to profitability remains unclear.

The cost reduction trajectory matters critically. Manufacturing costs dropped roughly 40% from 2022 to 2023, falling from $50,000-$250,000 USD to $30,000-$150,000 USD per unit. Unitree’s $5,900 USD pricing suggests further compression is possible—but only for simplified designs optimized for specific tasks rather than general-purpose capability.

The companies betting on general-purpose humanoids face a different cost structure: sophisticated AI systems, advanced sensors, precision actuators, robust safety systems, extensive testing, and regulatory compliance. These requirements don’t compress as easily as commodity components.

What iRobot’s Collapse Reveals

The bankruptcy filing exposes the structural challenges facing hardware robotics companies. iRobot spent $400 million USD on stock buybacks over its history—capital that could have funded product development or manufacturing expansion. Creditsafe analysis showed the company paying vendors three to four weeks late starting in May 2025, with credit scores dropping to “Very High Risk” by June.

But the deeper problem was strategic positioning. iRobot controlled a protected market niche for two decades, generating comfortable returns while incrementally improving the Roomba. When Chinese competitors entered with comparable technology at lower prices, iRobot had no moat. Patents bought time but not safety. Innovation slowed while competitors iterated.

The Amazon acquisition would have provided capital and strategic support to compete globally. Regulators blocked it, arguing it would harm competition. Instead, iRobot bankrupted and transferred to its Chinese manufacturer—exactly the outcome regulators claimed to prevent.

Co-founder Helen Greiner called the situation “heartbreaking” and questioned why transferring American robotics IP and market share to a Chinese manufacturer generated so little public concern. Angle termed it “a tragedy” and warned it should serve as a cautionary tale for competition watchdogs.

For humanoid investors, the lesson is sharper: regulatory risk compounds technical and market risks. Companies betting on acquisition exits face uncertainty. Companies betting on organic growth need sustainable competitive advantages against lower-cost competitors. Most current humanoid startups have neither.

The China Factor

China’s approach to humanoid robotics follows the playbook that crushed iRobot. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology implemented a 2023-2025 plan to build a complete innovation ecosystem from core components to system integration. Direct subsidies average 17.5% of equipment costs. Protected home markets let companies refine products before export.

The results speak clearly. Over 150 Chinese companies now develop humanoid platforms. UBTECH secured $1 billion USD in strategic financing and a $37 million USD contract to deploy Walker S2 robots for border patrol at the Vietnam border starting December 2025—marking the first large-scale government deployment. Galbot raised $300 million USD in December 2025, reaching $3 billion USD valuation with deployments in over 30 cities.

Western companies face a coordination problem. Figure’s $39 billion USD valuation depends on a consortium of strategic investors—Microsoft, OpenAI, Nvidia, Intel, Bezos, Salesforce. This creates alignment challenges: each investor has different strategic priorities, different timelines, and different definitions of success. Chinese companies with government backing and aligned domestic investors move faster with less friction.

The supply chain dynamics compound the problem. China controls an estimated 70% of component supply chains for robotics. Western companies source actuators, sensors, and manufacturing capacity from the same suppliers building competing Chinese humanoids. This creates both cost disadvantages and strategic vulnerabilities.

What Happens Next

Brooks predicts that successful robots in 15 years will have wheels, multiple arms, specialized sensors—and still be called “humanoid robots” despite abandoning human form. The prediction makes economic sense: wheels are cheaper and more reliable than legs, multiple specialized appendages outperform general-purpose hands for specific tasks, and purpose-built sensors beat attempts to replicate human perception.

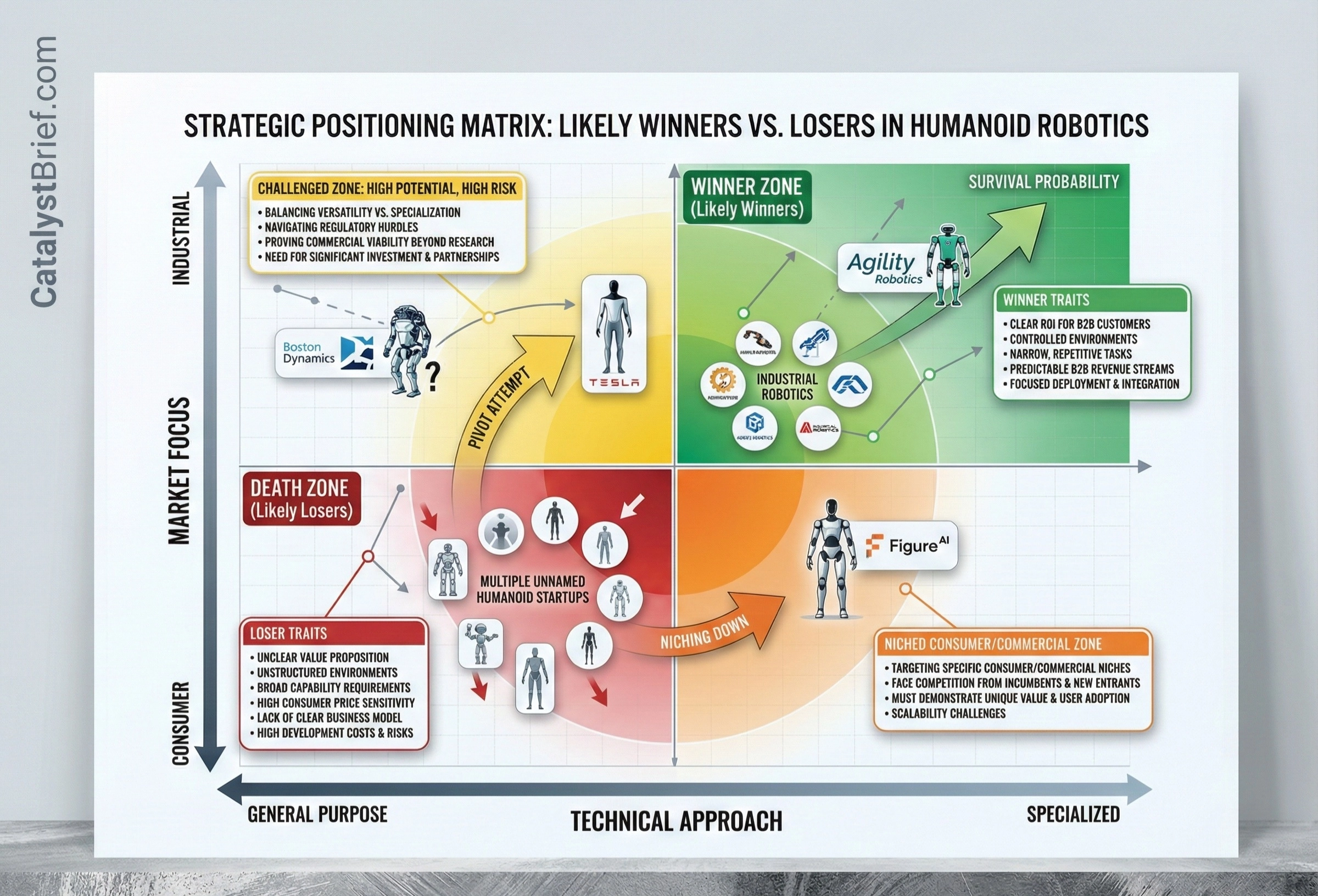

Agility Robotics’ Digit—deployed in Amazon and GXO warehouses—validates this approach. The robot handles boxes up to 35 pounds in controlled environments, walking at human speed and navigating obstacles. But Digit is built for a specific task in a specific environment. It doesn’t fold laundry, make coffee, or handle arbitrary household chores.

This defines the near-term viable path: specialized robots optimized for narrow industrial tasks in controlled environments. Warehouse logistics, manufacturing assembly, inspection work, material handling. These applications have clear ROI calculations, tolerance for imperfect performance, and existing industrial safety frameworks.

The companies pursuing general-purpose humanoids for home use face much longer timelines. Home environments are unstructured, tasks vary enormously, safety requirements are stringent, and price sensitivity is high. Goldman Sachs forecasts consumer applications lag industrial deployment by 2 to 4 years, with earliest consumer adoption around 2028 to 2030 in very limited capacities.

The funding environment will determine how many companies survive to compete in that eventual market. Crunchbase data shows $6 billion USD raised through mid-2025, putting the sector on track to exceed 2024 levels. But funding alone doesn’t guarantee outcomes.

The Humanoids Summit revealed the gap between aspiration and capability. Small robots roamed pouring lattes while evangelists discussed transformative AI techniques. But full-size prototypes were scarce. Demonstrations remained tightly controlled. The path from impressive demos to deployable products at scale remains unclear.

The Dot-Com Parallel

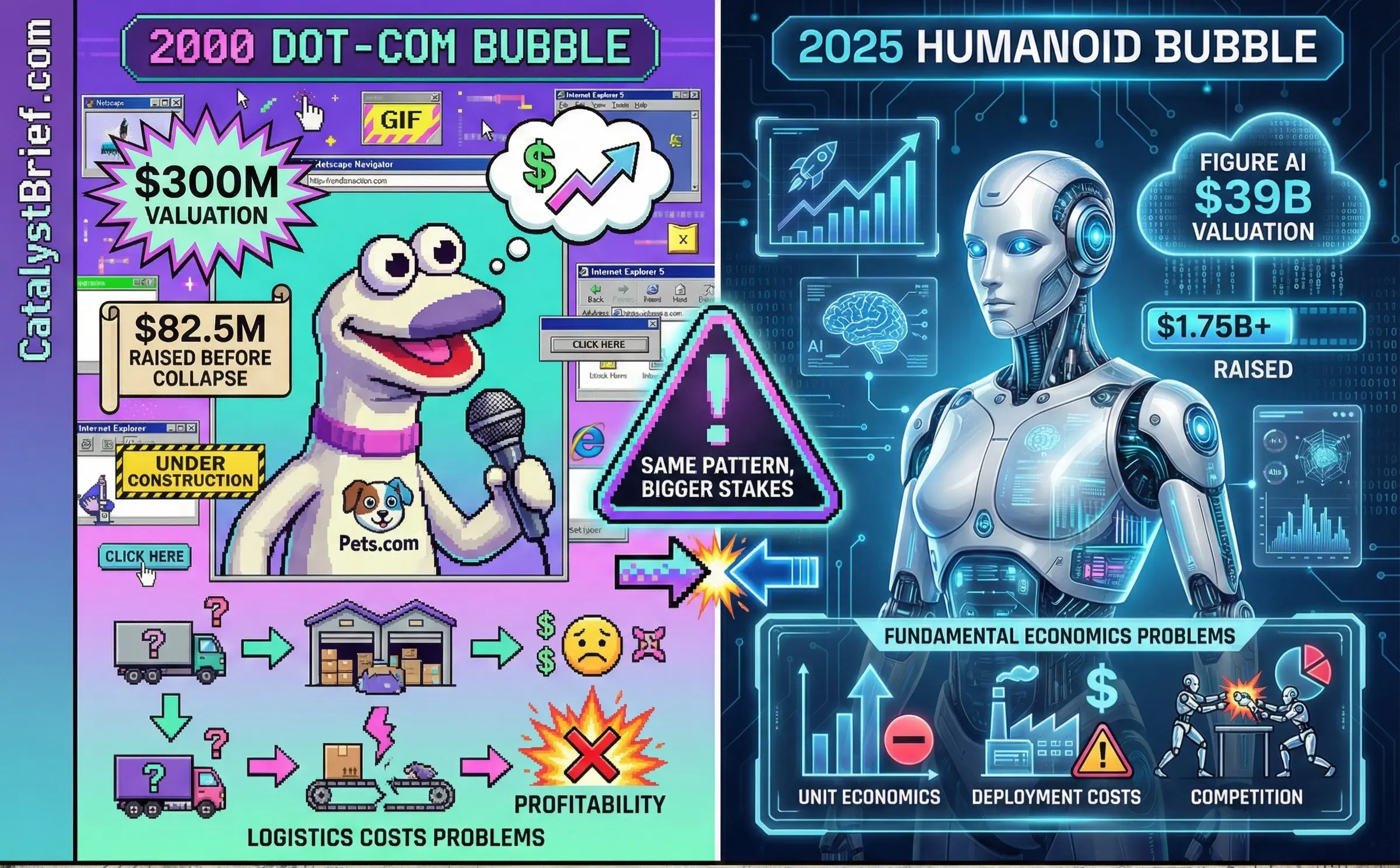

The parallels to the dot-com bubble are striking and instructive. In 2000, Pets.com commanded a $300 million USD valuation selling pet supplies online. The company collapsed when logistics fundamentals—warehousing costs, shipping economics, customer acquisition expenses—proved unworkable at scale. The business model assumed growth would solve unit economics. It didn’t.

Today’s humanoid startups face similar dynamics. Figure’s $39 billion USD valuation assumes robots will eventually generate revenue justifying that price. But the path from current capabilities to revenue-generating deployment remains speculative. Like Pets.com, the assumption is that scale will solve fundamental economic problems.

The difference is scale of capital at risk. Pets.com raised roughly $82.5 million USD before failing. Figure alone has raised over $1.75 billion USD. The entire humanoid sector has consumed nearly $10 billion USD. When the correction comes—and Brooks argues it’s inevitable—the wealth destruction will dwarf the dot-com era’s robotics casualties.

Some survivors will emerge. Amazon failed in its first years but ultimately dominated e-commerce. Google launched after the bubble burst and built the most valuable internet company. The robotics winners from this cycle may not even exist yet—just as Google didn’t exist during the first internet bubble.

But here’s the critical insight: the survivors won’t look like current leaders. Amazon succeeded by obsessing over logistics economics, not by assuming scale would fix fundamentals. Google won by solving search technically better than competitors, not by raising the most capital. The humanoid winners will likely follow a similar pattern: solving specific technical or economic problems that current approaches miss.

Brooks suggests the winners will abandon human form entirely. Wheels instead of legs. Multiple specialized arms instead of two general-purpose hands. Custom sensors instead of human-like perception. Companies building these “humanoid” robots—in name only—will compete against purists building true bipedal androids.

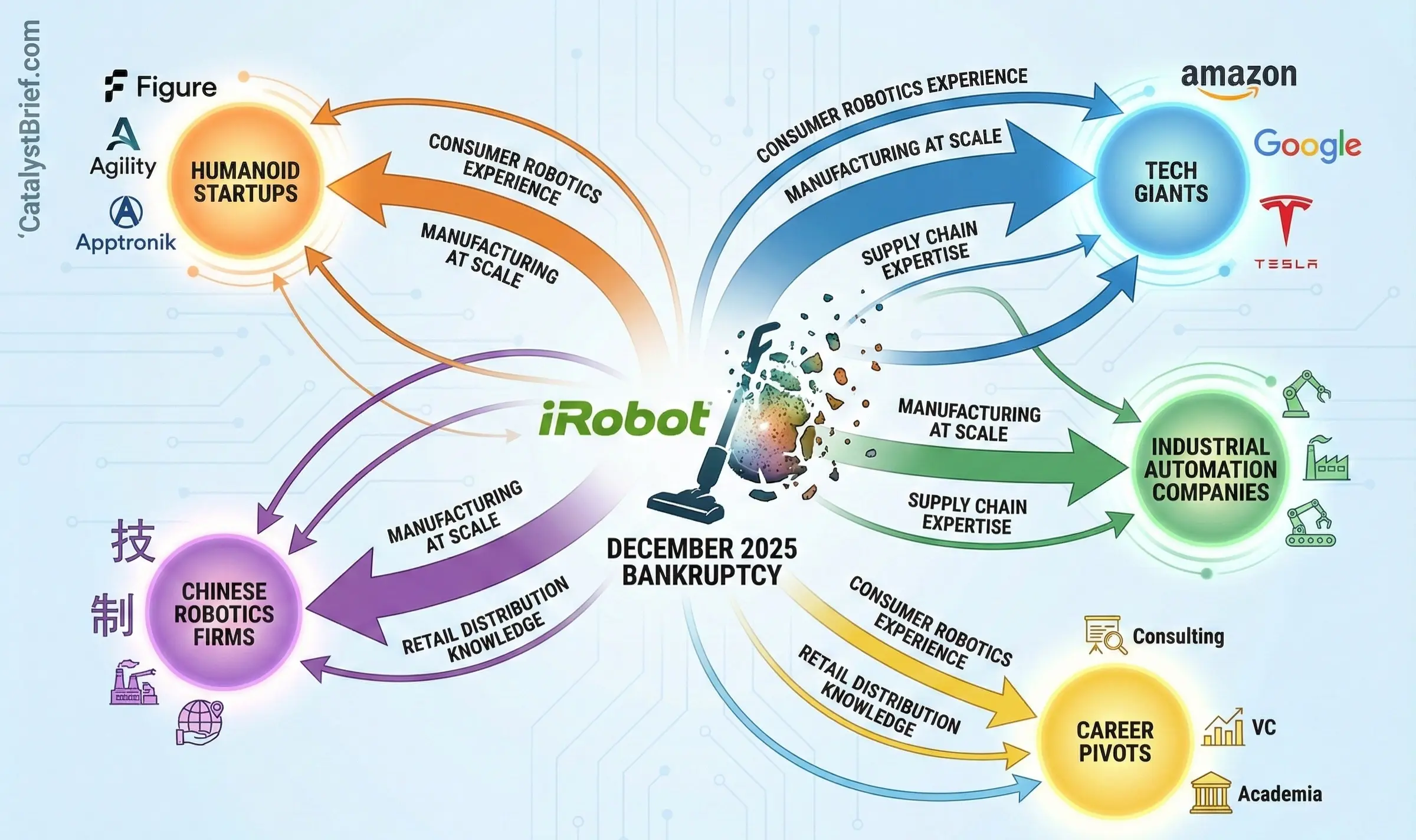

The Talent Migration Question

iRobot’s bankruptcy has scattered experienced consumer robotics talent across the industry. Where do they go? Some will join humanoid startups, bringing hard-won lessons about manufacturing, supply chain, customer support, and retail distribution. Others will migrate to industrial automation, where economics already work.

This talent flow matters because consumer robotics and industrial robotics require different expertise. iRobot engineers know how to design robots for uncontrolled home environments, handle warranty support at consumer scale, and navigate retail distribution. These skills transfer directly to home humanoid development.

But Apptronik, Agility, and other industrial-focused companies need different capabilities: fleet management software, facility integration, industrial safety compliance, and B2B sales models. The skill sets overlap but don’t perfectly align.

The companies that successfully recruit ex-iRobot talent gain institutional knowledge about what doesn’t work. iRobot’s bankruptcy followed specific strategic failures: underestimating Chinese competition, overrelying on patent protection, pursuing stock buybacks instead of R&D investment, and losing the innovation race on features like wet mopping.

Every mistake iRobot made, humanoid companies risk repeating. The talent that lived through those failures brings invaluable pattern recognition. Smart companies will debrief ex-iRobot engineers extensively and incorporate those lessons into strategy.

The Regulatory Wild Card

iRobot’s bankruptcy stemmed partially from regulatory intervention blocking the Amazon acquisition. This creates precedent for humanoid companies planning acquisition exits. The Federal Trade Commission and European Commission both opposed the deal, arguing it would reduce competition and harm consumers.

The outcome—iRobot bankrupt and acquired by its Chinese manufacturer—demonstrates regulatory risk. Well-intentioned intervention produced exactly the result regulators claimed to prevent: reduced competition and transfer of American technology to foreign ownership.

Humanoid companies face amplified regulatory uncertainty. Safety standards don’t exist for bipedal robots in consumer or commercial environments. Liability frameworks remain undefined. Privacy regulations haven’t addressed mobile robots with cameras and sensors collecting data in homes and workplaces.

These questions will require years to resolve through standards bodies, regulatory agencies, and likely court cases after inevitable accidents. Companies deploying robots before clear frameworks exist face both opportunity and risk: first-mover advantages versus legal exposure.

The international dimension compounds complexity. China’s government actively supports robotics development through subsidies, procurement, and regulatory frameworks. European regulators focus on safety and privacy. American agencies balance innovation promotion with consumer protection. No harmonized global approach exists.

Companies must navigate this fragmented landscape while competing globally. Products developed for Chinese markets may not meet European safety standards. Solutions optimized for American liability regimes may be uncompetitive on cost. The companies that successfully navigate these regulatory differences gain sustainable advantages.

The Investment Implications

For engineers, the technical challenges represent career opportunities. Building tactile sensing systems, developing manipulation algorithms, creating safety frameworks, and optimizing actuator designs all require deep expertise over long timeframes. Companies will need this talent regardless of which specific platforms succeed.

For managers and executives, the strategic question is make versus buy. Partner with robotics companies for specific applications, invest in component suppliers that benefit regardless of which platform wins, or develop internal capabilities for specialized automation needs? The answer depends on industry, scale, and timeline.

For investors, Brooks offers a specific prediction: “a lot of money will have disappeared” over the next 15 years. The companies that survive will look different from today’s leaders. Some current high-flyers will fail completely. Others will pivot to specialized applications. A few might actually deliver on general-purpose capabilities—but on timelines measured in decades, not years.

The broader pattern holds: robotics deployment takes far longer than anyone imagines. Self-driving cars—another Brooks prediction target—remain limited to specific cities and conditions despite billions in investment. Humanoids face harder technical challenges, more complex safety requirements, and less forgiving economics.

iRobot’s bankruptcy provides the template: initial success, comfortable market position, failure to adapt to new competition, blocked strategic exit, financial deterioration, and asset transfer to lower-cost competitors. Replace “Chinese vacuum manufacturers” with “Chinese humanoid companies” and the script remains the same.

The question isn’t whether humanoid robots will eventually work at scale. The question is which companies survive long enough to participate in that future, and whether current valuations reflect realistic timelines to profitability.

Brooks has spent 35 years building robots and watching predictions fail. His company just validated his concerns by collapsing despite market leadership and 50 million units sold. The humanoid investors betting against his latest warnings should explain why their robots will fare better than his Roombas.

The Catalyst’s Take

I predict that within 18 months, at least three humanoid companies valued above $1 billion USD will declare bankruptcy, be acquired for less than half their peak valuation, or pivot away from general-purpose humanoids.

The iRobot bankruptcy proves Brooks’ thesis. His company—with market leadership, 50 million units sold, and Amazon’s attempted rescue—still couldn’t survive Chinese competition.

If Brooks couldn’t save the robotics company he built, founders with harder technical problems won’t fare better just because they’ve raised more capital. Capital buys time, not solutions to fundamental physics and economics.

Companies burning $100 million+ USD annually on general-purpose home humanoids without revenue within 36 months face iRobot’s fate: too much overhead, too little revenue, competitors offering better prices.

We’re watching the robotics version of 2000’s internet bubble. Some Amazons will emerge. But most investors are betting on Pets.com equivalents. Brooks just gave the clearest warning: his own company’s corpse.