China deploys Walker S2 humanoid robots at Vietnam border crossing as embodied intelligence transitions from factory floors to public infrastructure

The Brief

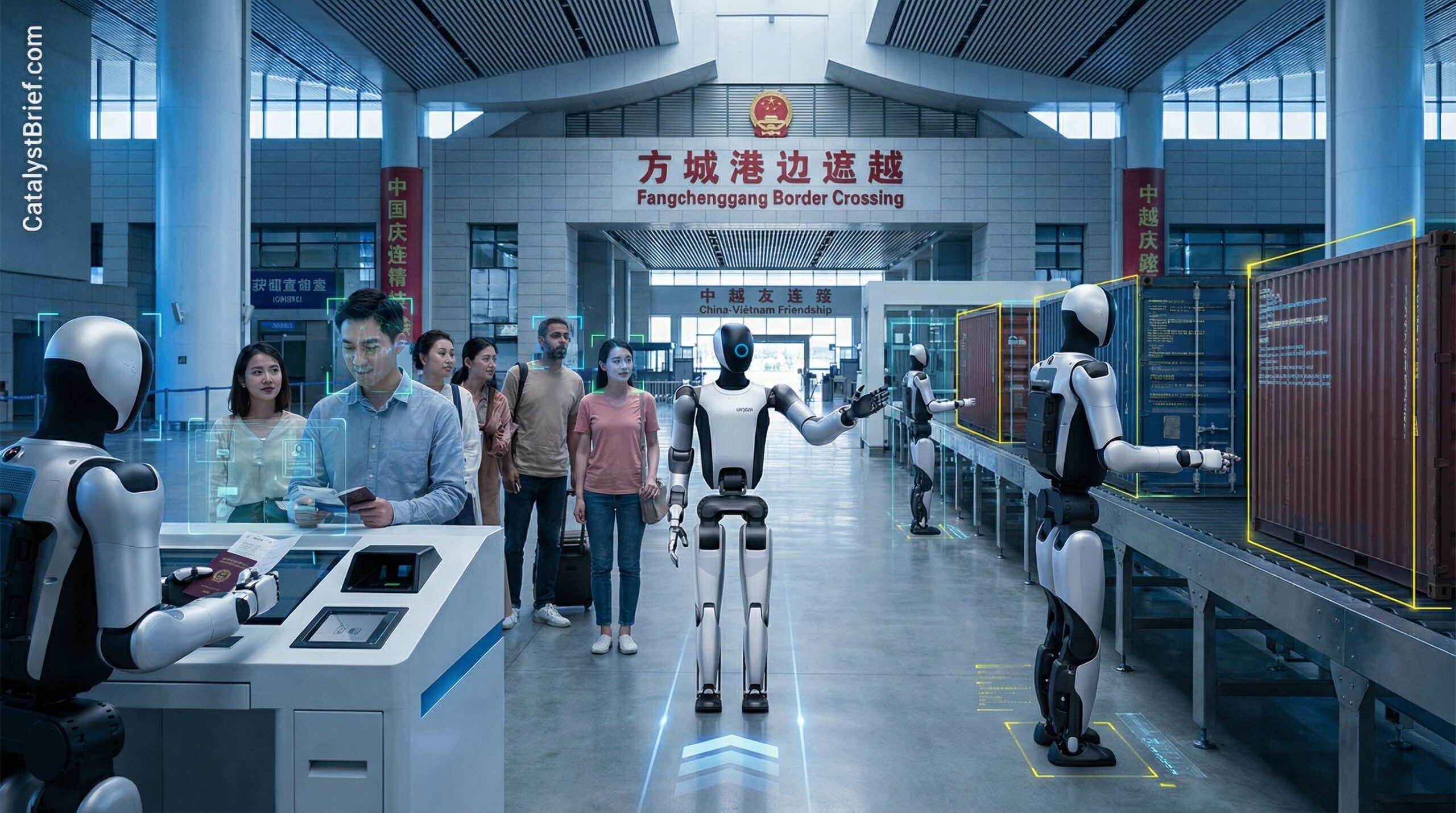

The News: China has begun deploying humanoid robots at the Fangchenggang border crossing with Vietnam under a $37 million USD contract awarded to Shenzhen-based UBTECH Robotics. The Walker S2 robots started arriving in December 2025 to assist border officials with passenger guidance, vehicle direction, crowd monitoring, and cargo inspection.

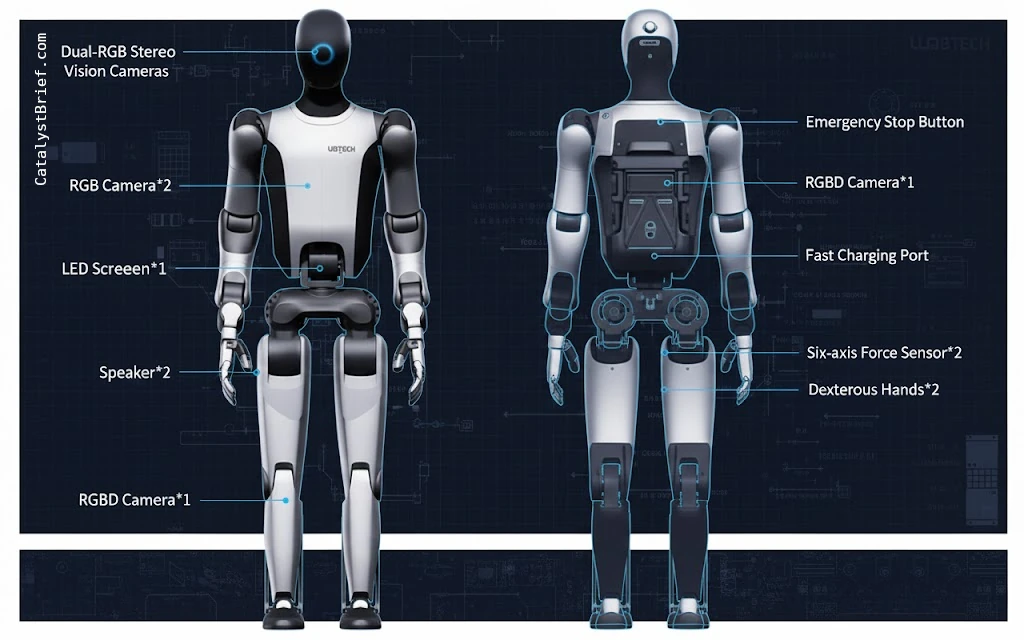

The Stats: The Walker S2 stands 1.76 meters tall with 52 degrees of freedom and can handle 15-kilogram payloads. Its autonomous battery-swap system enables near-continuous 24/7 operation by replacing depleted batteries in 3 minutes without human assistance. UBTECH reports cumulative 2025 orders approaching $157 million USD for the Walker S2 series, with deployment at one of the busiest China-Vietnam transit points handling millions of annual crossings.

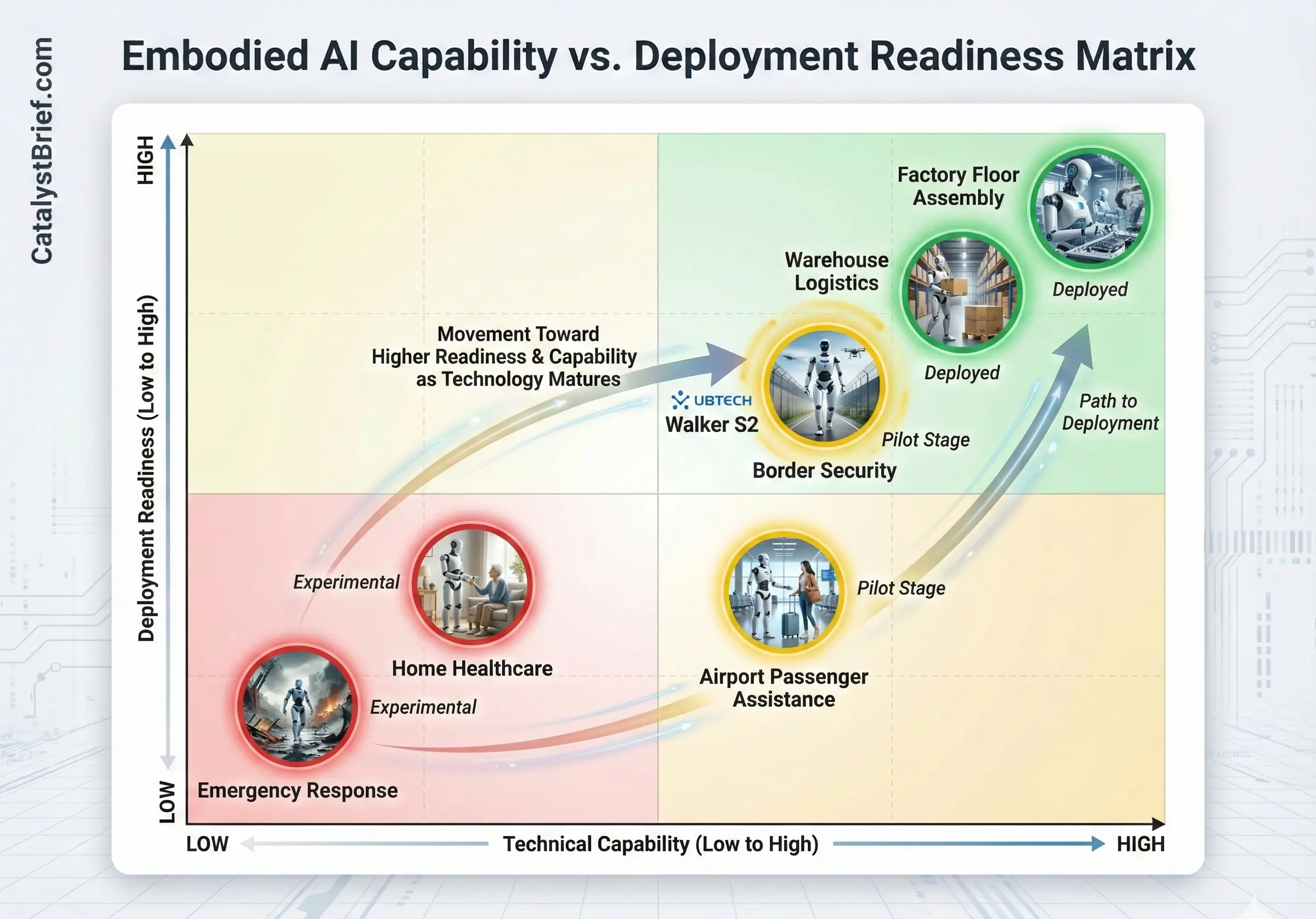

The Bottom Line: Embodied AI has moved from controlled factory environments into unpredictable public infrastructure, where robots must navigate dense crowds, interpret ambiguous human behaviour, and maintain operational continuity in mission-critical government operations. The border deployment represents a foundational test case for whether artificial intelligence embedded in physical robots can reliably augment human decision-making in high-stakes security contexts.

The Catalyst

The coastal city of Fangchenggang in Guangxi province sees constant movement. Cargo trucks loaded with Vietnamese textiles roll northward while southbound convoys carry Chinese electronics and machinery. Passenger coaches cycle through immigration queues as day travellers cross for business meetings or family visits. The rhythms are relentless, the schedules unforgiving. Any slowdown in inspections ripples through supply chains spanning Southeast Asia.

This December, a new category of worker arrived to support the border officials managing this flow. The Walker S2 humanoid robots from UBTECH Robotics began operations under a $37 million USD government contract, marking one of the first large-scale deployments of such technology in law enforcement and public security operations.

Standing 1.76 meters tall with jointed legs, articulated arms, and a rotating torso, these machines look unmistakably humanoid. But their significance extends beyond physical resemblance. They represent what researchers call embodied artificial intelligence: AI systems that don’t just process information in data centers but operate in physical robot bodies, navigating messy real-world environments where lighting changes, people move unpredictably, and objects appear in unexpected places.

The deployment raises immediate questions about whether embodied AI is ready to leave the controlled environment of factory floors and enter the chaotic realm of public infrastructure. The answer carries implications for how governments worldwide might deploy autonomous systems in contexts where reliability and accountability are non-negotiable.

Why Borders Test Embodied Intelligence

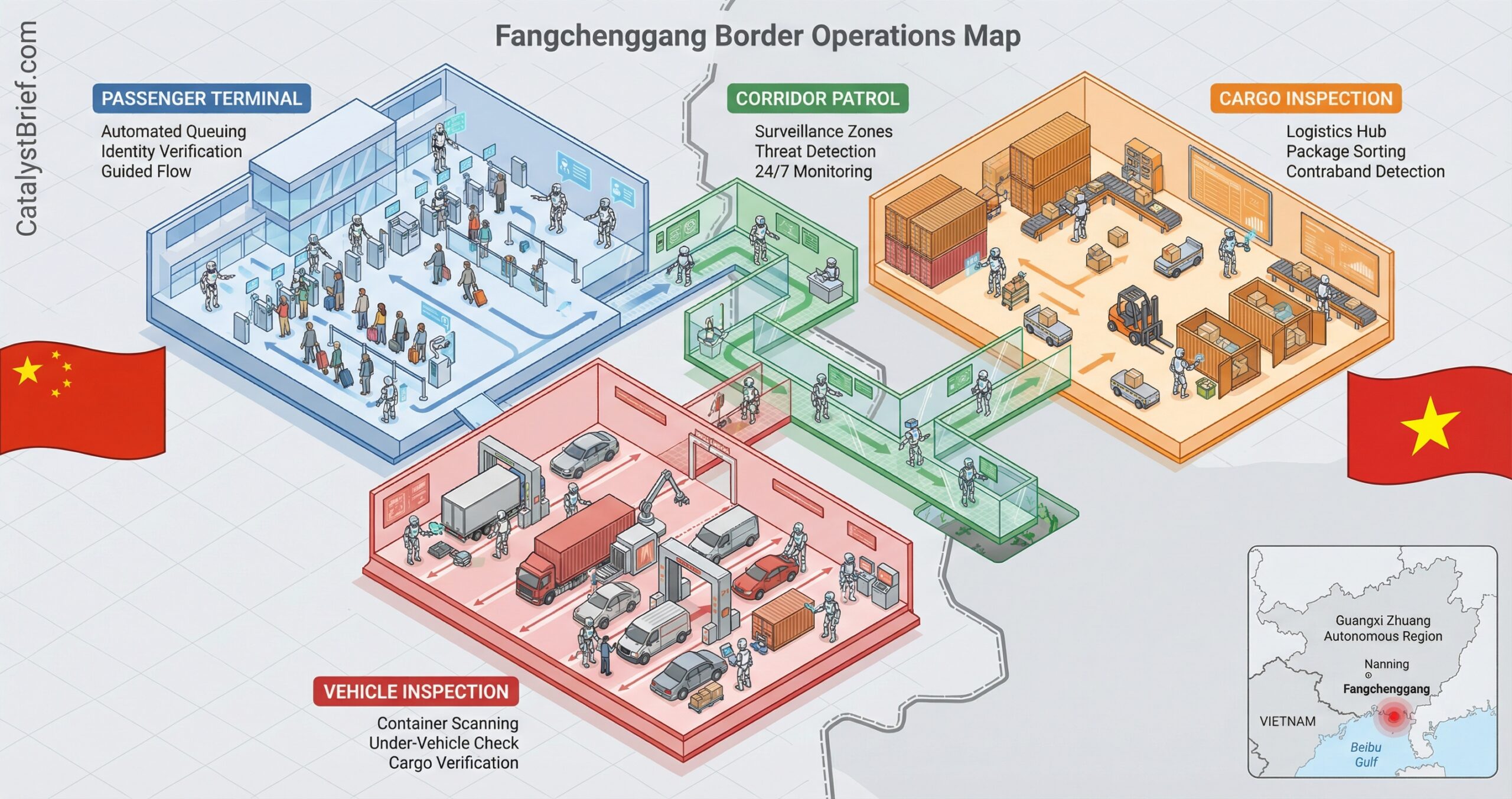

Chinese planners selected the Fangchenggang crossing deliberately. It operates on tight schedules with minimal tolerance for delays. Inspection workflows must adapt constantly as cargo manifests change, passenger volumes fluctuate, and security protocols evolve in response to emerging threats. The environment demands that systems handle both routine operations and unexpected exceptions without grinding operations to a halt.

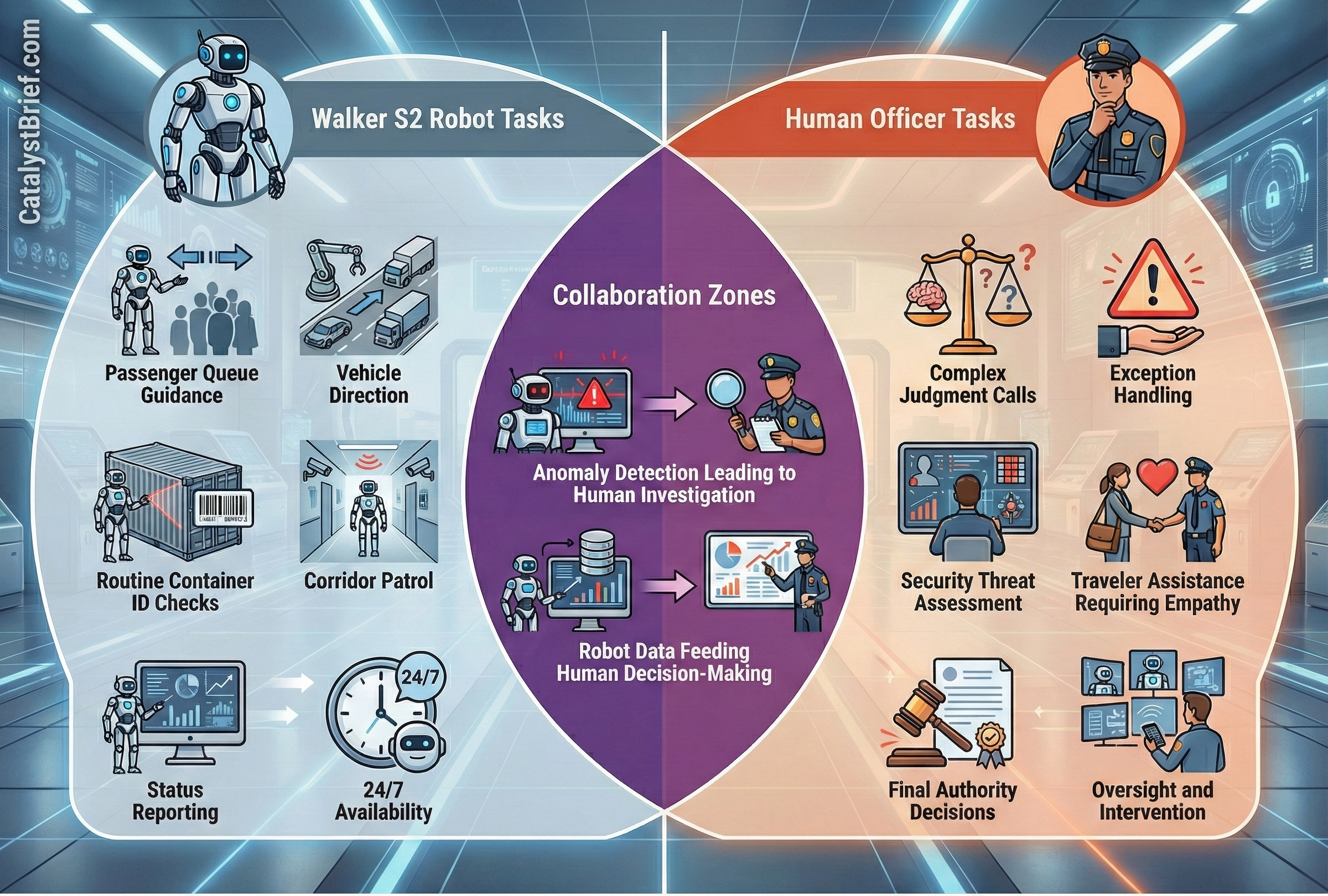

The Walker S2 robots will guide passenger queues, direct vehicle traffic, and answer basic traveler questions. Some units will patrol corridors and waiting areas, monitoring for blocked emergency exits or crowd patterns that might require human officer intervention. Others will work within cargo lanes, supporting logistics teams by checking container identification numbers, confirming security seals, and relaying status updates to central dispatch.

Beyond the border checkpoint itself, portions of the robot fleet are expected to inspect industrial facilities for steel, copper, and aluminum, walking predetermined routes through high-temperature manufacturing yards where human inspectors face heat exposure and repetitive strain injuries. The breadth of deployment scenarios tests whether a single platform can generalize across vastly different operational contexts without extensive reprogramming.

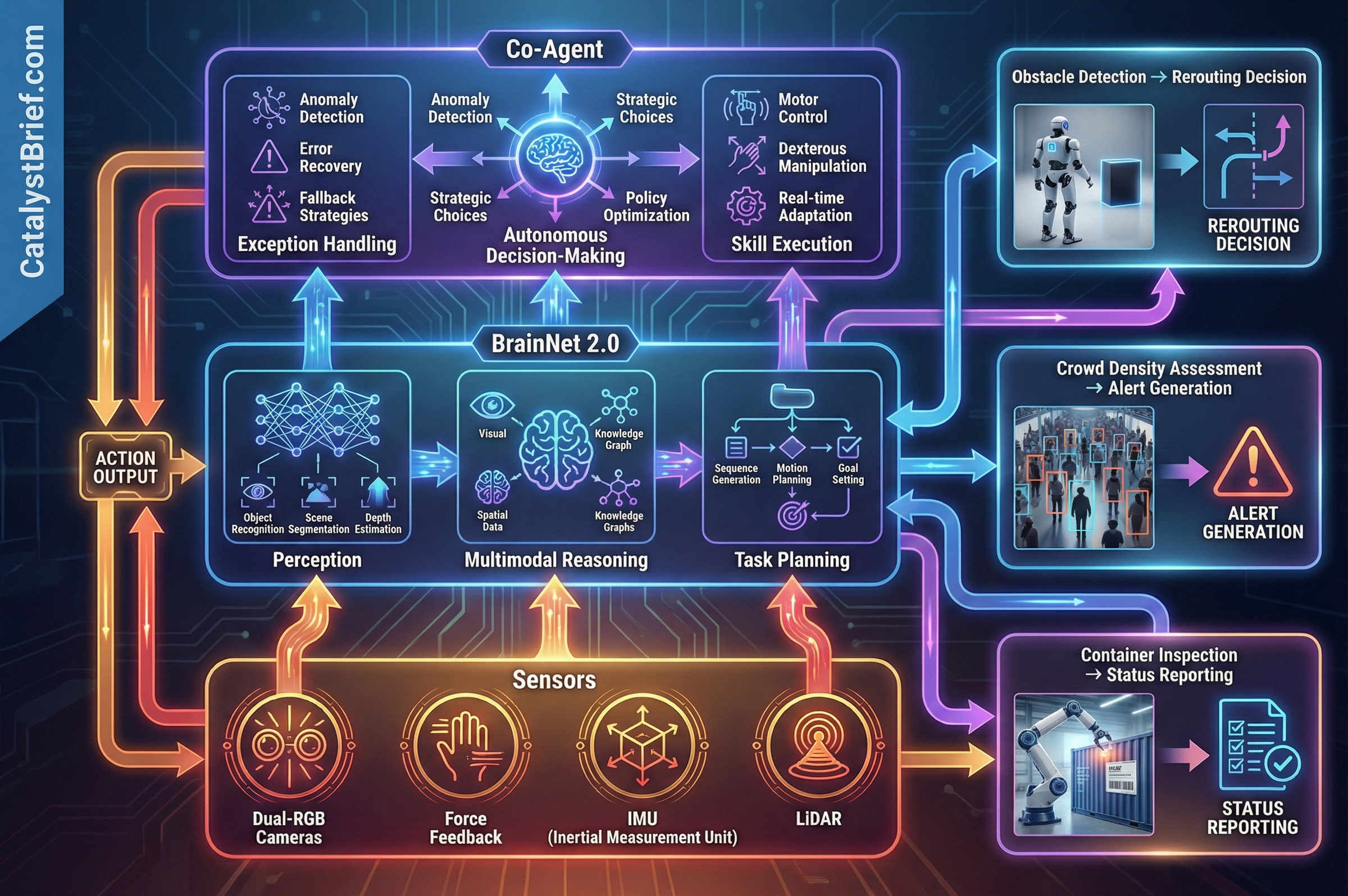

This operational flexibility hinges on UBTECH’s BrainNet 2.0 and Co-Agent AI frameworks, which combine multimodal reasoning, autonomous task planning, and real-time exception handling. The system uses dual-RGB stereo vision cameras to provide human-like depth perception, fusing visual data with force-feedback sensors in the robot’s joints to maintain balance while carrying loads or navigating uneven surfaces. When the robot encounters an unexpected obstacle—a passenger’s luggage blocking a walkway, or a cargo container positioned incorrectly—the AI must decide whether to route around it, wait for human guidance, or alert supervisors to the anomaly.

These split-second decisions reveal the core challenge of embodied AI: bridging the gap between perceiving the environment and acting appropriately within it. Unlike digital assistants that offer suggestions users can accept or reject, embodied systems commit to physical actions with real consequences. A miscalculation in load distribution could damage cargo. A navigation error could disrupt passenger flow. An incorrect assessment of crowd density could delay security response when human officers are most needed.

The Operational Economics of Continuous Uptime

Perhaps the most technically audacious feature of the Walker S2 is its autonomous battery-swap capability. The robot can detect when power levels drop below operational thresholds, navigate to a dedicated battery exchange station, remove the depleted power pack using coordinated dual-arm movements, and install a fresh battery—all within approximately 3 minutes and without human intervention.

This capability addresses a fundamental constraint in robotics deployment: downtime. Traditional industrial robots that require 90-minute charging cycles lose productivity during those windows. For a border operation running 24 hours daily, those gaps translate directly into reduced throughput. The autonomous hot-swap system changes the calculation. With near-continuous operation achieving over 98 percent availability, deployment economics shift substantially.

Consider the staffing implications. A human border officer works standard shifts with mandated breaks and annual leave. Sustaining 24/7 coverage requires multiple officers to cover a single position. A robot capable of continuous operation with only 3-minute power interruptions reduces the number of units needed to maintain the same coverage, potentially lowering operational costs over multi-year deployment horizons.

The dual-battery architecture enables this performance. The robot runs on one battery while monitoring the charge state of both packs. When the active battery approaches depletion, the system switches to the backup, providing operational continuity while it navigates to the charging station. If alignment at the docking bay proves imperfect, the robot adjusts its position using visual feedback and force sensors until the battery module locks securely. Safety interlocks halt all joint motion within 200 milliseconds if the battery fails to engage correctly, preventing mechanical damage or operational hazards.

These technical details matter because they reveal where embodied AI succeeds and where it still struggles. The Walker S2 handles the predictable aspects of battery management with impressive autonomy. But the system still requires pre-positioned charging infrastructure, standardized battery modules, and fail-safe protocols designed by human engineers. The robot executes the swap reliably, but humans created the conditions that make reliability possible.

China’s Strategic Bet on Physical AI

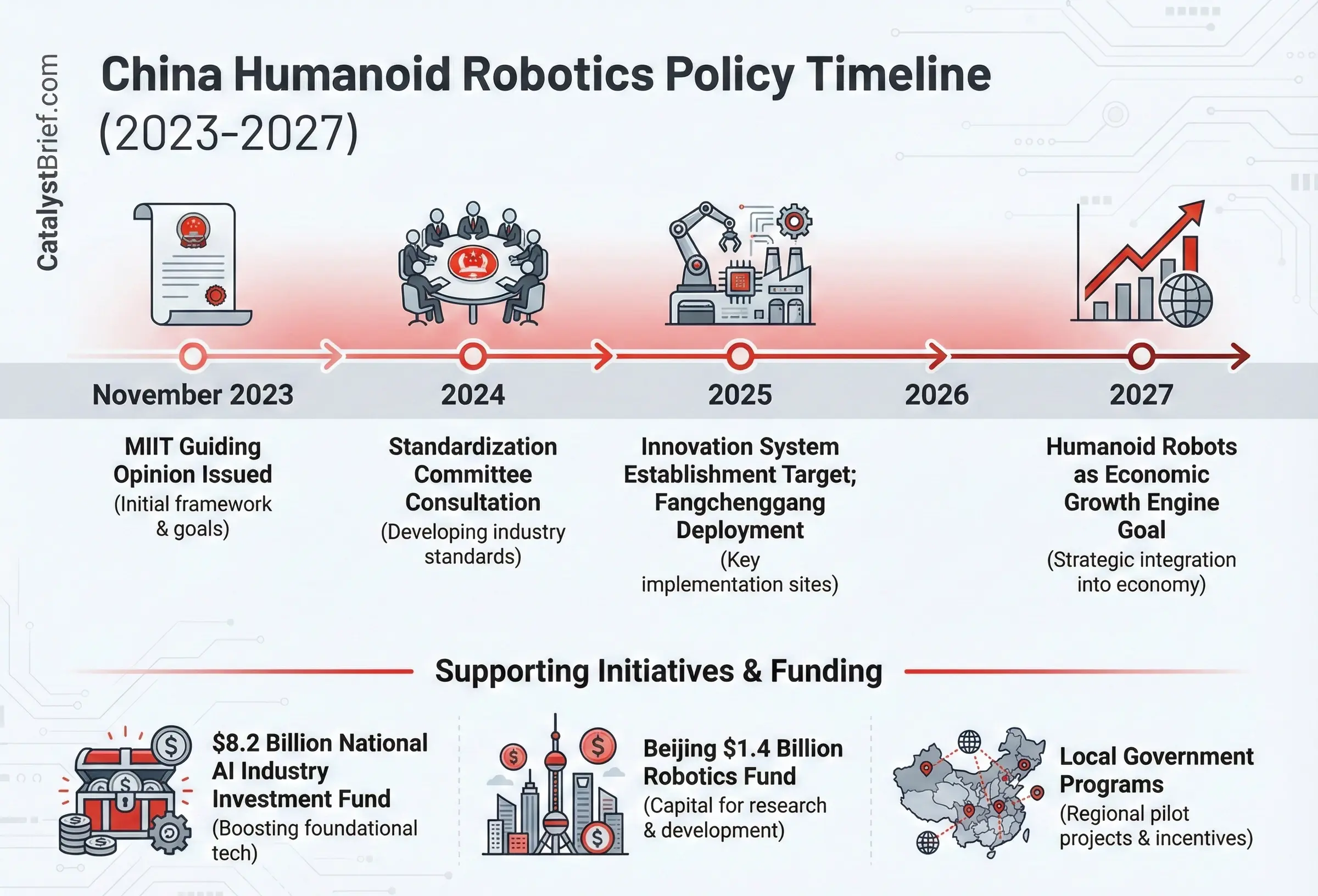

The Fangchenggang deployment extends China’s broader industrial policy around embodied intelligence. In November 2023, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology issued guidance calling for China to establish a humanoid robot innovation system by 2025 and position these technologies as an important engine of economic growth by 2027. The ministry opened consultation in 2024 on a standardization technical committee tasked with writing industry rules for humanoid robots, inviting company leaders from UBTECH and other domestic firms onto national standard-writing bodies.

This policy infrastructure reflects calculations about demographic and economic pressures. China faces declining working-age populations and labor shortages in manufacturing, logistics, and service sectors. Embodied AI offers a potential response: deploying robots where human workers are scarce or where tasks pose safety risks. The border trial at Fangchenggang fits this agenda, putting humanoids into a regulated space where safety, reliability, and accountability will be monitored closely by government regulators.

The timing also reflects confidence in China’s robotics supply chain. After years of depending on foreign suppliers for core components like servo motors, sensors, and controllers, Chinese manufacturers have built significant domestic capabilities. UBTECH sources much of the Walker S2 hardware from Chinese suppliers, reducing exposure to potential supply disruptions or technology export restrictions. The vertical integration provides operational flexibility but also aligns with national objectives around technology self-sufficiency.

Industry data suggests the strategy is gaining traction. UBTECH reports that 2025 orders for the Walker S2 series exceed $157 million USD when combining the Fangchenggang border contract with earlier deals covering factories and data centers in other Chinese provinces. The company remains unprofitable despite rising revenue, facing pressure to demonstrate that growing order books can translate into sustainable margins as production scales.

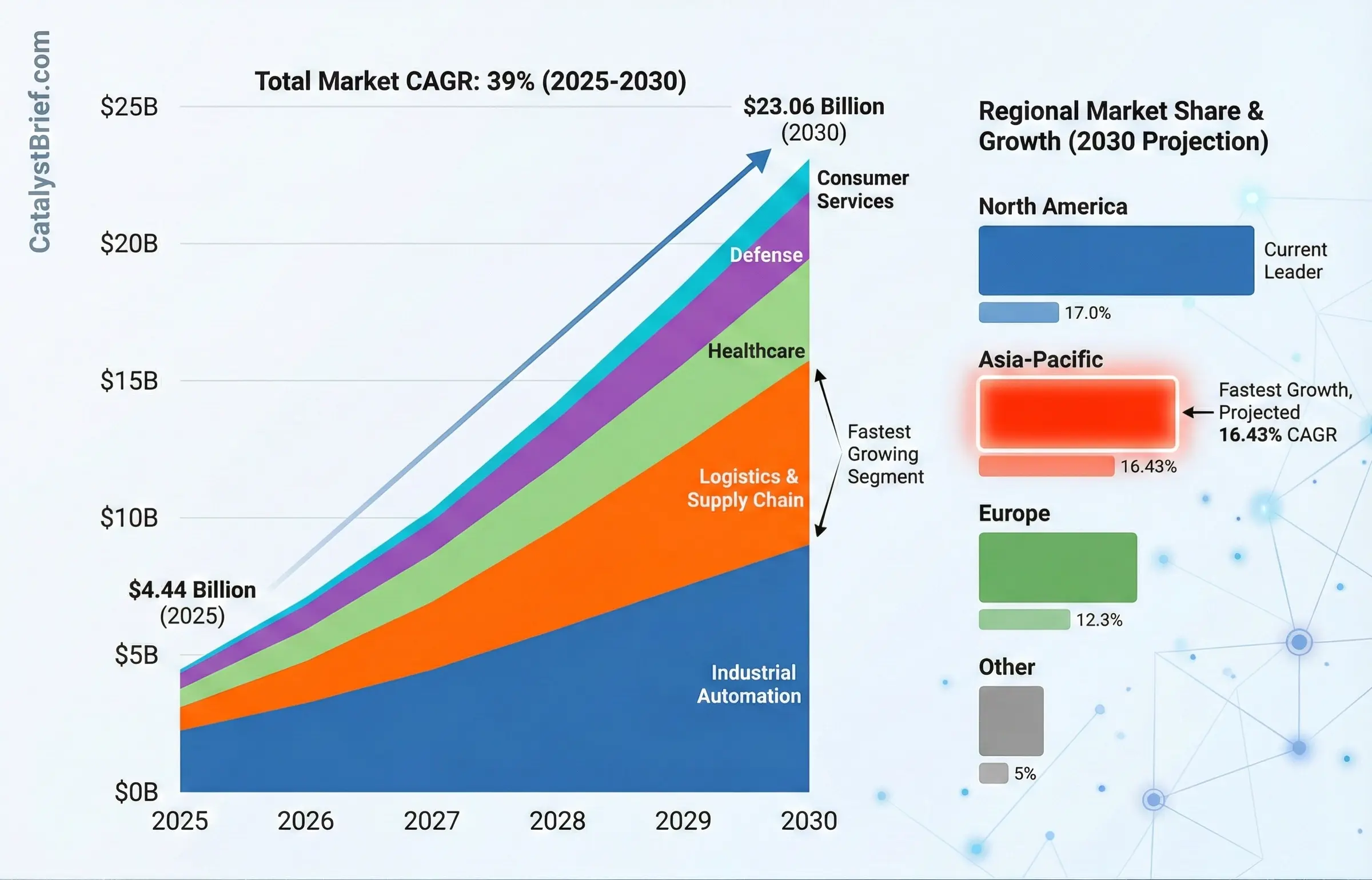

Globally, the embodied AI market is projected to expand from $4.44 billion USD in 2025 to $23.06 billion USD by 2030, representing a compound annual growth rate near 39 percent. Multiple sectors are driving this growth: manufacturing operations seeking flexible automation, logistics networks deploying autonomous mobile robots for warehouse operations, healthcare facilities using robots for patient monitoring and medication delivery, and now government operations exploring robots for public safety and infrastructure management.

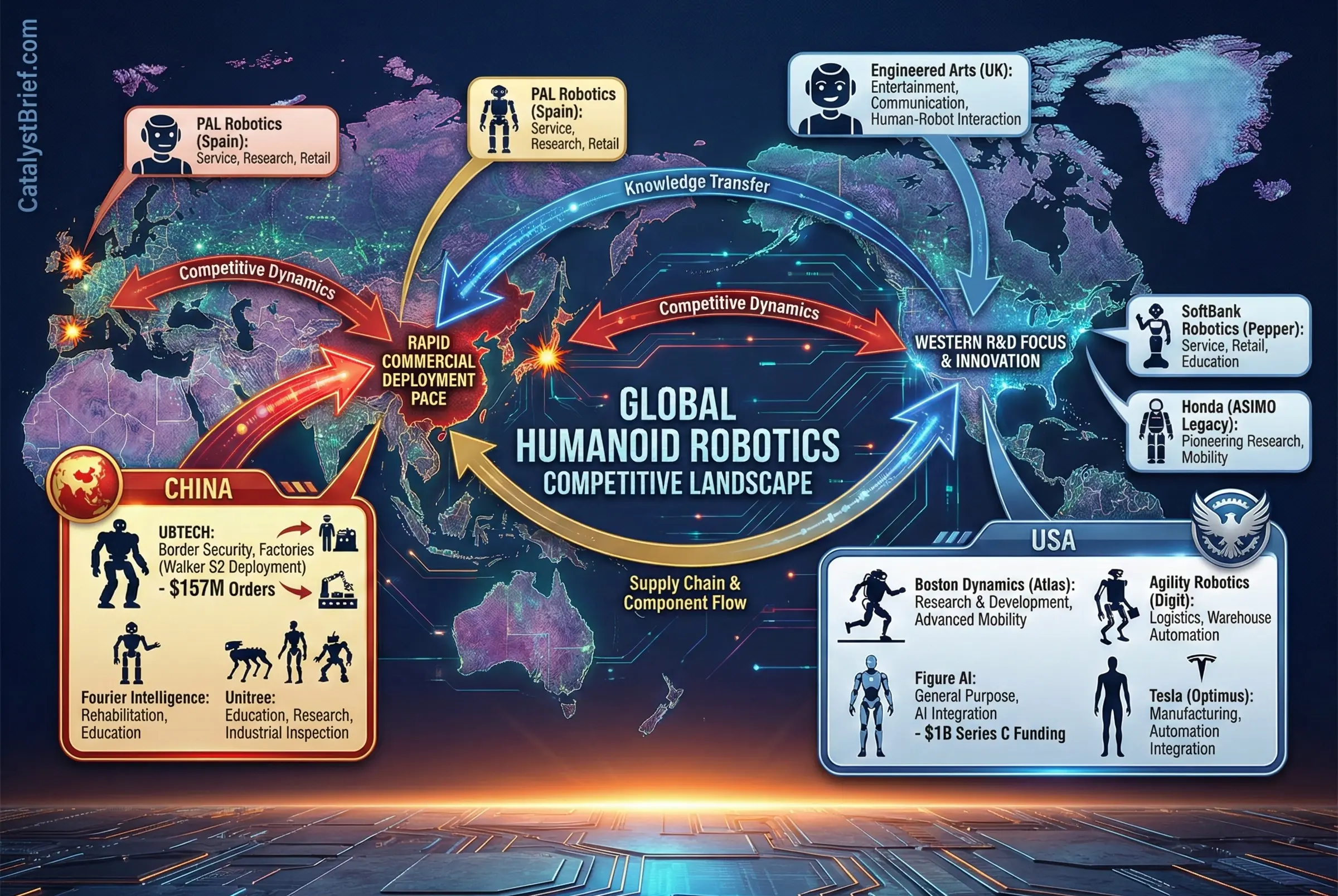

North America currently leads in research and development, with companies like Boston Dynamics, Agility Robotics, and Figure AI attracting substantial venture investment. But Asia-Pacific markets, particularly China, are accelerating commercial deployments. The region benefits from established electronics supply chains, government support for robotics adoption, and cultural readiness for human-robot collaboration in service roles. The Fangchenggang deployment exemplifies this pattern: moving quickly from prototype demonstrations to operational field trials in high-visibility government applications.

The Trust Problem in Public Spaces

When embodied AI systems operate in factories, the environment is structured to accommodate them. Floors are level, lighting is consistent, objects appear in predictable locations, and safety zones keep humans and robots separated during potentially hazardous operations. When those same systems enter public spaces like border crossings, the assumptions collapse.

Passengers arrive with unexpected baggage configurations. Vehicles park at inconsistent angles. Lighting conditions change as cloud cover shifts. Children dart unpredictably. Elderly travelers need extra assistance. Cargo containers arrive with non-standard labeling. Every deviation from expected patterns tests whether the robot’s AI can generalize from its training data to handle novel situations safely.

This generalization challenge explains why the border deployment is as much a regulatory test as a technical one. Chinese officials are treating it as a pilot program that will inform future standards. If the robots perform reliably—guiding passengers without creating bottlenecks, inspecting cargo without damaging containers, detecting anomalies without generating excessive false alarms—it strengthens the case for broader deployment at airports, seaports, and train stations. If performance proves inconsistent, regulators gain empirical evidence about where human oversight remains essential.

The accountability questions extend beyond technical performance. When a human border officer makes a judgment error, existing legal and administrative frameworks govern the response. When a robot contributes to an error—misidentifying a security risk, delaying a time-sensitive shipment, or failing to detect a genuine threat—responsibility becomes ambiguous. Did the error stem from flawed software, inadequate training data, mechanical failure, poor environmental conditions, or misuse by human supervisors?

China’s approach involves maintaining human officers in oversight roles while robots handle routine tasks. The division of labor positions robots as augmentation tools rather than replacements. But as robots take on more responsibilities and human supervisors manage larger fleets, the practical boundaries between augmentation and substitution may blur. At what point does the human become the backup system rather than the primary decision-maker?

These questions lack settled answers because embodied AI in public security is genuinely new. The Fangchenggang deployment will generate operational data that informs how governments worldwide think about deploying autonomous systems where public safety is paramount. Other countries will watch to see which tasks robots handle well, where they struggle, what kinds of failures occur, and how Chinese officials respond when problems arise.

Implications for the Global Robotics Landscape

The Walker S2 deployment signals that embodied AI is transitioning from niche applications into mainstream infrastructure. This shift creates pressure on competing robotics companies to demonstrate similar capabilities. Boston Dynamics, Tesla, Agility Robotics, and Figure AI are all developing humanoid platforms targeting industrial and commercial markets. None have announced deployments comparable in scale or visibility to the Fangchenggang border operation.

The competitive dynamic extends to technical capabilities. UBTECH’s autonomous battery-swap system represents a genuine engineering achievement that addresses a real operational constraint. Competitors will need to match or exceed this capability to compete for customers who prioritize uptime. The same applies to AI perception systems, manipulation precision, and navigation reliability. As one company demonstrates a capability in field deployment, market expectations shift. What seemed impressive in controlled demonstrations becomes table stakes for commercial viability.

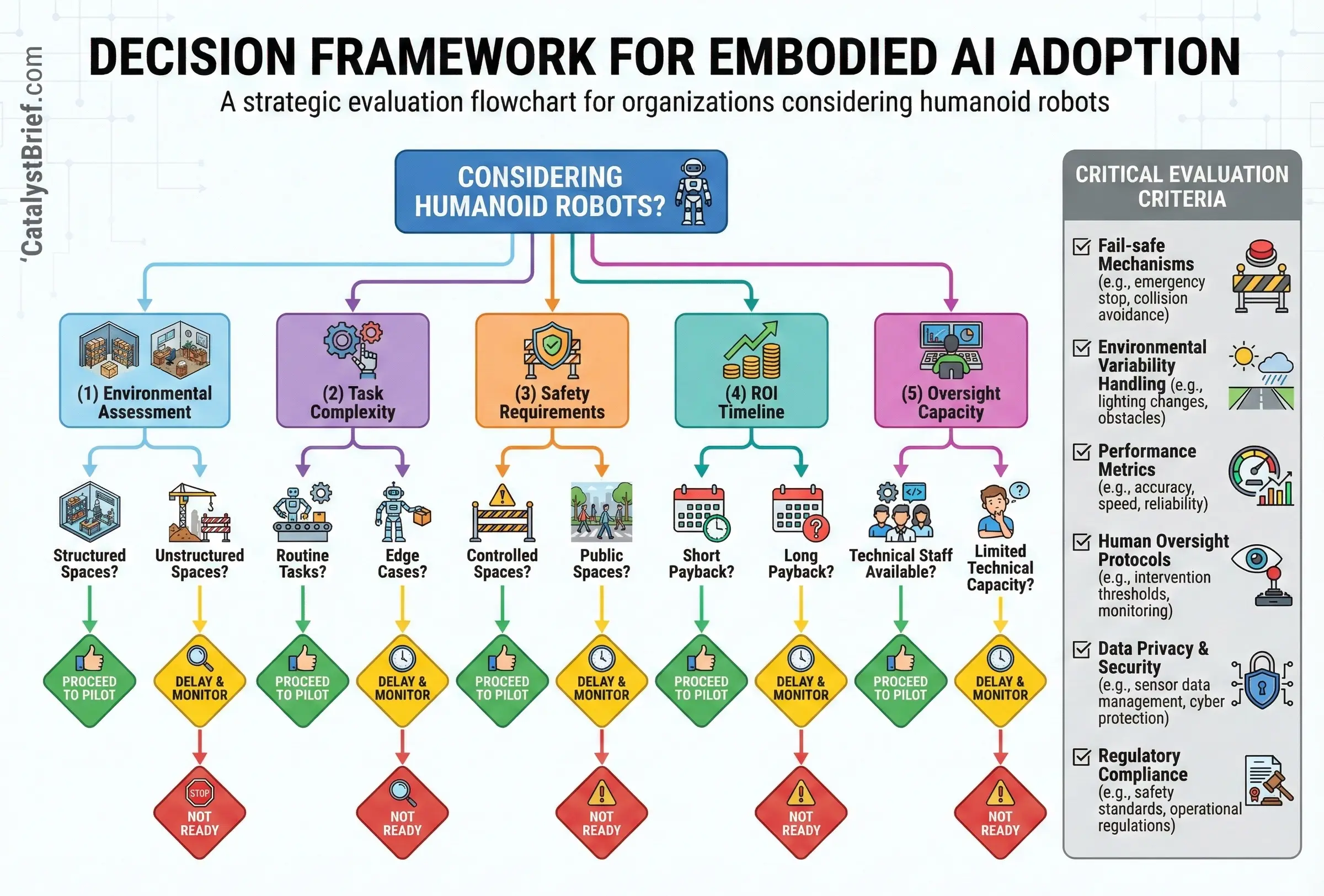

This competitive escalation should drive innovation but also raises risks. Companies facing pressure to match competitor capabilities might deploy systems before fully validating performance in operational contexts. The robotics industry lacks the mature regulatory frameworks that govern aviation or pharmaceuticals, where extensive testing precedes public deployment. Embodied AI is moving faster than regulatory adaptation, creating gaps where accidents might reveal weaknesses only after they cause harm.

For professionals navigating technology careers, the Fangchenggang deployment offers multiple lessons. First, embodied AI is emerging as a distinct discipline requiring expertise in mechanical engineering, computer vision, AI reasoning, and human-robot interaction design. Engineers who can work across these domains will find growing opportunities as deployment scales. Second, the field is internationalizing rapidly. China’s aggressive commercialization, North America’s research leadership, and Europe’s regulatory focus on AI safety create different innovation dynamics that professionals should understand. Third, the gap between laboratory demonstrations and operational deployments remains substantial. Systems that work reliably in structured environments often fail in unpredictable real-world conditions. Engineers who excel at bridging that gap will become increasingly valuable.

For organizations considering embodied AI adoption, the deployment highlights questions to ask. Can candidate systems handle the environmental variability of your operational context? Do they include fail-safe mechanisms that prevent catastrophic failures? What human oversight will be required, and do you have staff with appropriate skills? How will you measure performance, and what thresholds will trigger reassessment? What happens when robots encounter edge cases outside their training data?

The Walker S2 robots working at Fangchenggang won’t answer these questions definitively. But they will generate empirical evidence about what embodied AI can and cannot reliably accomplish when deployed in complex, high-stakes environments. That evidence will shape the next wave of adoption decisions across industries and geographies.

What Comes Next

If the border deployment succeeds, expect accelerated rollouts across Chinese public infrastructure. Airport security, railway stations, and port facilities present similar operational profiles: high throughput requirements, security sensitivity, and labor-intensive routine tasks that robots could potentially handle. Success at Fangchenggang provides proof points that reduce perceived risk for subsequent deployments.

Internationally, governments will weigh the strategic implications. Robotics capabilities increasingly factor into assessments of national competitiveness alongside traditional measures like manufacturing capacity and technological innovation. Countries that deploy embodied AI effectively in public services may gain operational advantages in efficiency, consistency, and cost management. Countries that lag may face pressure to catch up, potentially adopting systems before adequately addressing safety and accountability concerns.

The technology itself will continue evolving rapidly. Current limitations in robot perception, manipulation, and reasoning reflect the state of AI research circa 2025, not fundamental constraints. As training methods improve, compute becomes more powerful, and robots accumulate operational experience, their capabilities will expand. Tasks that seem beyond current systems may become routine within years.

But capability growth doesn’t automatically translate into wise deployment. The most important developments may be institutional rather than technical: establishing standards for testing embodied AI systems before public deployment, creating certification processes for robot operators and supervisors, developing legal frameworks that address liability when autonomous systems err, and ensuring that efficiency gains don’t come at the cost of surveillance overreach or erosion of human dignity.

The humanoid robots now working at the China-Vietnam border represent a threshold moment. Embodied AI is no longer confined to factories or warehouses. It’s entering public spaces where its actions affect people who didn’t choose to interact with robots and who may not understand how they work. Getting this transition right matters enormously. The Fangchenggang deployment is one of the earliest large-scale attempts. Its outcomes will influence how humanity navigates the emergence of intelligent machines operating physically alongside us.

The Catalyst’s Take

I predict that within 18 months, at least three major international airports will announce humanoid robot pilot programs for passenger assistance and security screening, directly citing the Fangchenggang deployment as proof of operational viability. The Chinese government will leverage this border trial to position itself as the global standard-setter for embodied AI safety protocols, publishing frameworks that other nations will adopt rather than develop independently.

More provocatively, we’ll see the first serious public safety incident involving an embodied AI system in a government operation before the end of 2026—not because the technology is inherently dangerous, but because deployment is outpacing the development of proper oversight mechanisms. The incident won’t slow adoption but will finally force long-overdue conversations about liability, transparency, and the appropriate boundaries for autonomous systems in contexts where human judgment has historically been irreplaceable.

The real inflection point isn’t technical capability. It’s institutional readiness. China is moving faster than Western democracies partly because centralized decision-making enables rapid deployment, but also because questions about privacy, surveillance, and algorithmic accountability receive less public debate. That asymmetry creates a competitive dynamic where Western firms face pressure to match Chinese deployment speed while operating under stricter scrutiny. We’re about to discover whether democratic oversight is a brake on innovation or essential protection against premature deployment of systems we don’t fully understand.